Japanese Photo Magazines after 1945:

The importance of the printed matter to Japanese photography cannot be overemphasized. The Japanese photobook is generally recognized as the pinnacle for artistic expression, not only for its innovative photography, but also for its graphic design and artisanal printing techniques. But long before the photobook, photographers aspired to see their images reproduced in the pages of a magazine. These periodicals were the main vehicle by which photography was disseminated in Japan.

Read the introduction or go directly to the magazines.

‘In a radio address to the Japanese people on August 15, 1945, emperor Hirohito accepted defeat, finally bringing to an end a war that had continued for almost 15 years.

For Japanese photographers, this also represented the end of a long “winter” during which they had been largely unable to obtain film stock and photographic paper, and, moreover, their freedom to take and publish photographs by a variety of restrictions.

Japanese cities had been devastated by air raids, and it would be a long time before distribution of food returned to normal, but the situation regarding photography recovered quickly. It was as if people first wanted to satisfy their hunger for expression and creation that had been suppressed for so long.’

(Iizawa Kōtarō: The evolution of postwar Photography.*)

A booming Japanese camera industry, as part of the economic recovery in the 1950s, resulted in a average production of more then 10.000 cameras per month and with a very affordable price, these cameras found their way to a large number of amateur photographers.

A technician at Nippon Kogaku ( Nikon ) factory at Ohi - Tokyo, inspecting lenses.

January 5, 1952. AP Photo/ Bob Schulz.

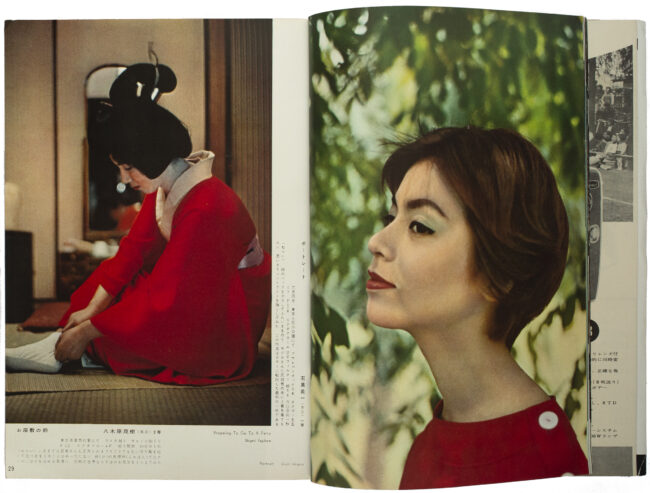

Amateur photo session of a model. Photo by Funayama Masaru, published in Camera Club , November 1954

Magazines like Asahi Camera (1949 - 2020), Camera Mainichi (1954 -1985), Nippon Camera (1950 - 2021) and Sankei Camera (1954 - 1964) were born from the need to provide information to these new photo enthusiasts.

Asahi Camera October 1949

Camera Mainichi June 1954

Nippon Camera 1952

Sankei Camera Mai 1954

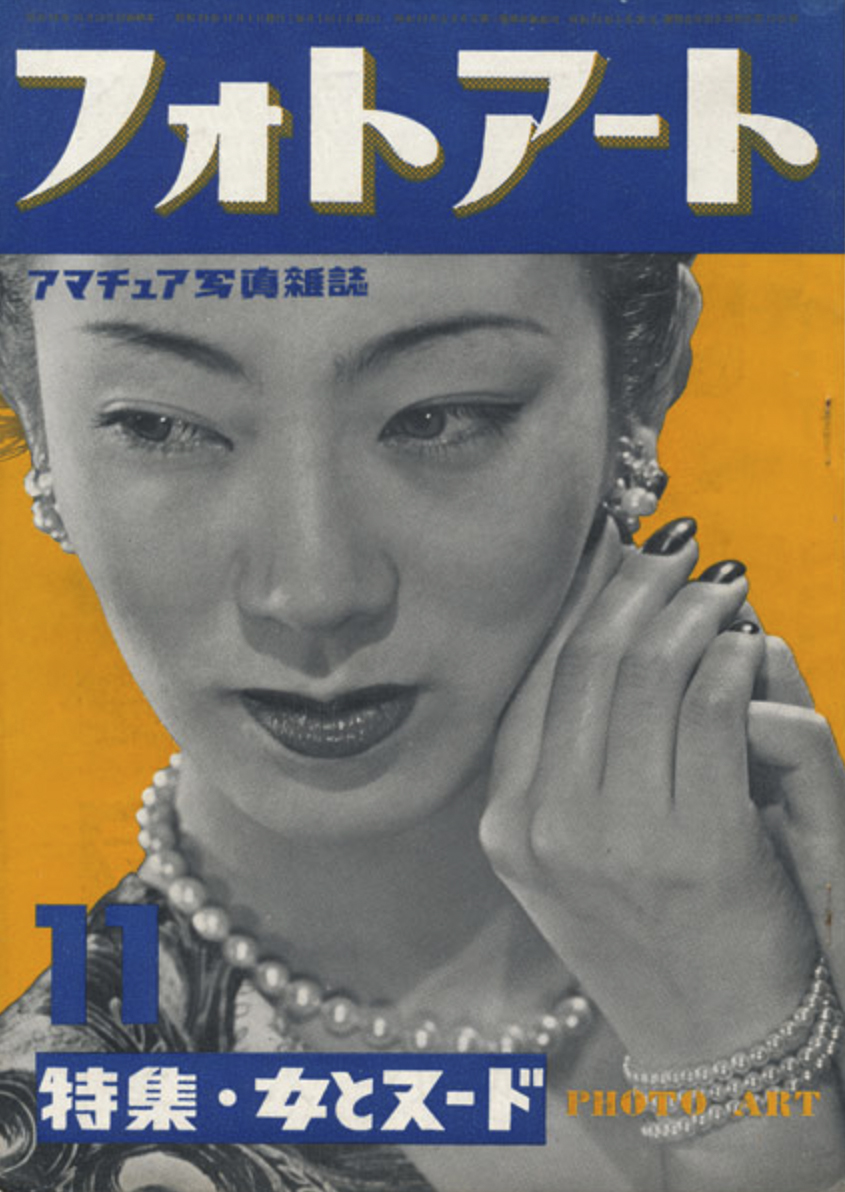

Photo Art November 1949

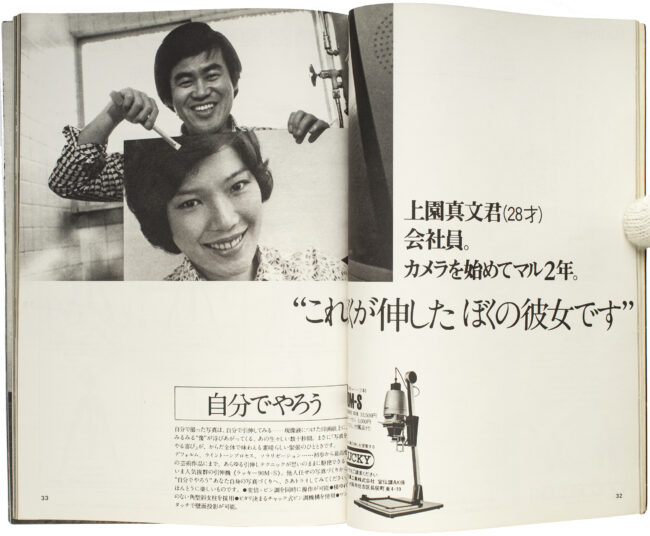

Although much of the content consisted of articles about technique or equipment, the new generation of Japanese photographers, in addition to the amateur 'snapshot taker' , was given plenty of space for their visual stories.

Lots of equipment, techtalk, phototechnique and know how.

Exposure meter built-in camera and good use of it.

Photo Art 1959-4

A new era is coming to domestic camera’s.

Sankei Camera 1960 -5

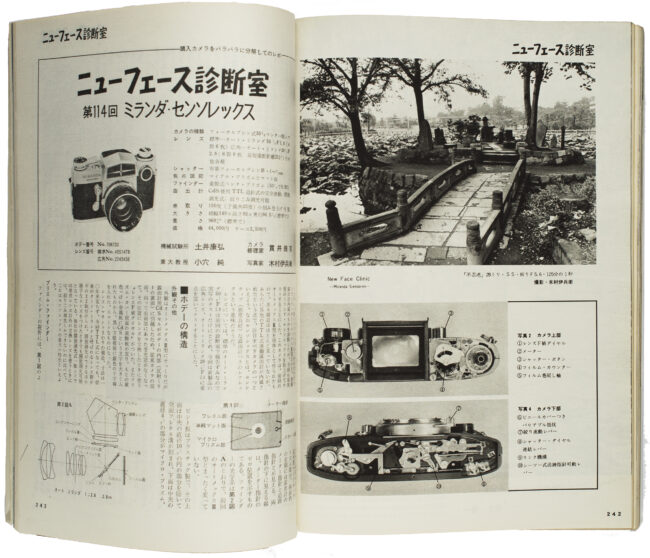

New Face Diagnosis Room; Miranda Sensorex

Asahi Camera 1966-12

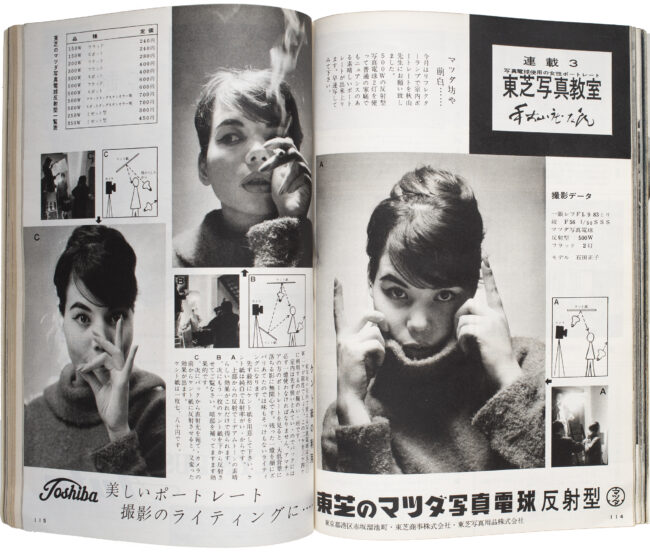

Female portrait using a photo bulb.

Asahi Camera 1959 -3

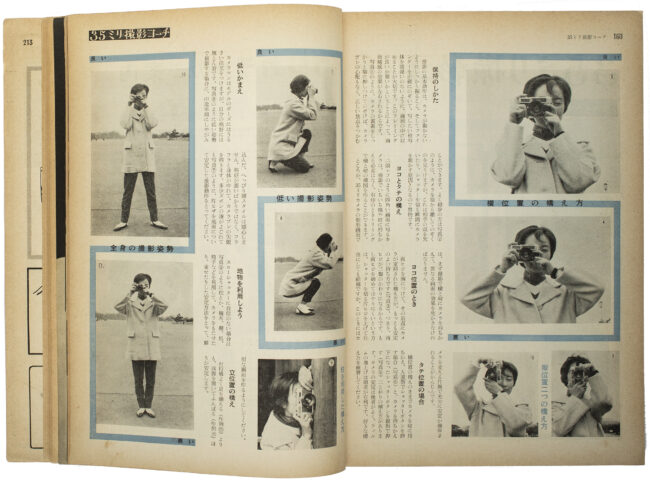

Camera coach; Points for holding the camera.

Camera Art 1960 -1

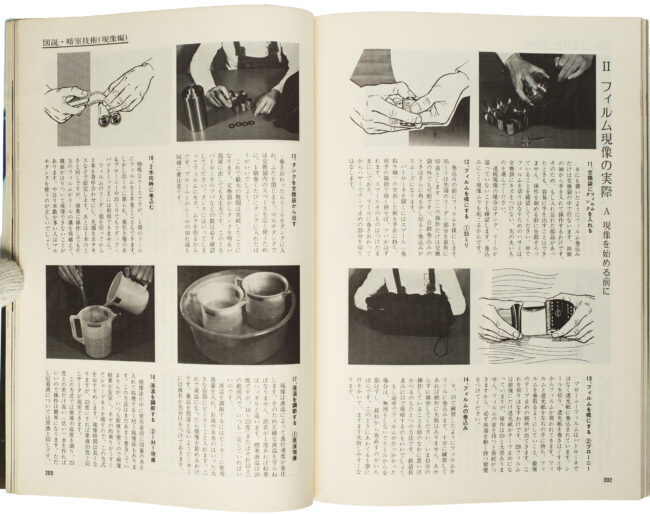

Film developing skills.

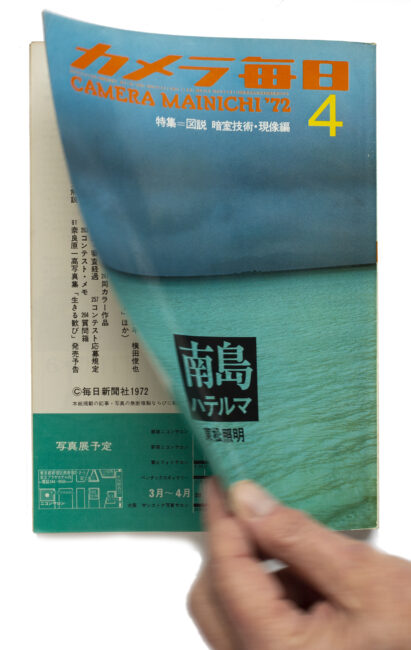

Camera Mainichi 1972 -4

But also space for a new generation of photographers.

‘Latest works of rising young photographers’;

7 pages in Camera Mainichi 1958 October issue

‘Rookie Salon’; 5 pages newcomer Ishiguro Kenji

in Sankei Camera 1959 May issue.

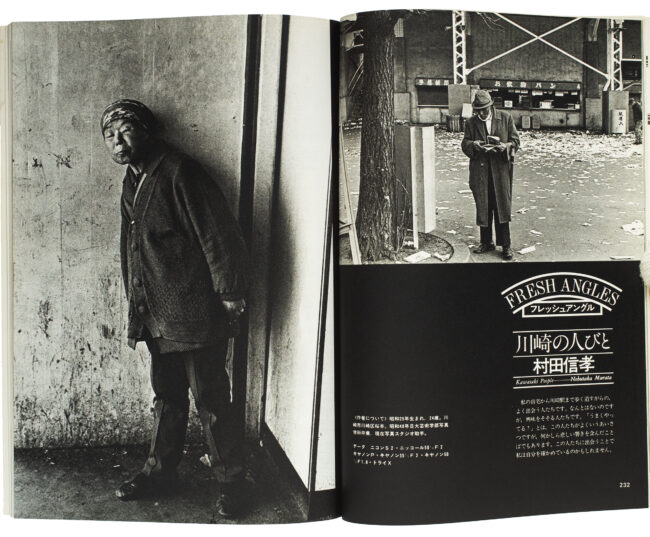

‘Fresh Angles’; works of 2 graduate students.

10 pages in Asahi Camera 1975 July issue.

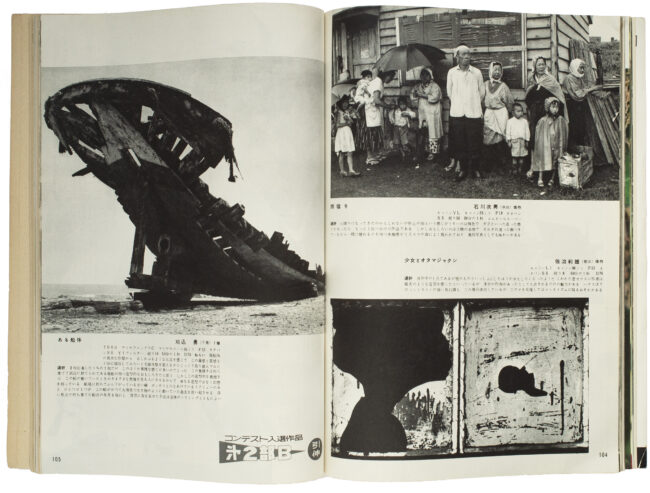

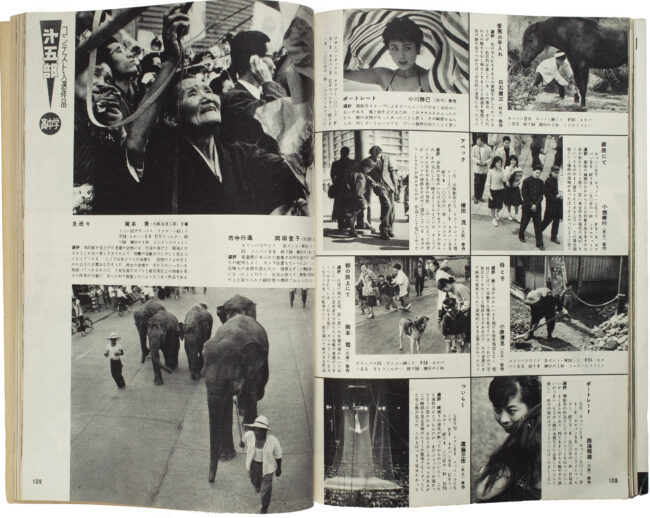

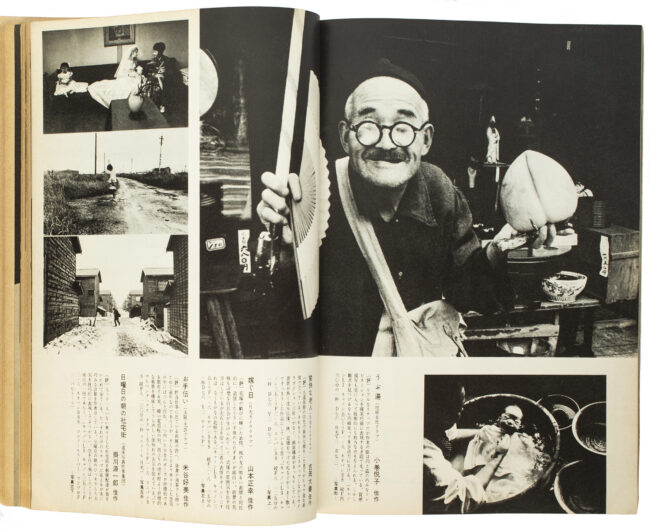

Most magazines had monthly photo contests which were actively participated in by photo enthusiasts.

These contests have been an integral part of Japanese photo magazines and they contributed to their immense popularity. For instance; the Camera Mainichi 1958 November issue had 1051 entries for only the color contest that month. Quite a few pages are dedicated to these contests and they exist in various categories. A magazine usually had 4 main catagories ( black and white large prints, b&w small prints, transparencies, color prints ) But many magazines had variations on these themes, like ‘three-piece essays’, or a contest for photoclubs. Some magazines even had special pages for the young amateurs.

Introduction to the contest in Camera Mainichi 1978:

“The Camera Mainichi Contest is a place for amateur photographers to present their work. At the same time it is also a place for beginners to improve their skills and test their skills. Please feel free to participate without being bound to previous contests.”

The selections and review discussions or comment ( mostly up to third prize ) is done by photographers and/or editorial staff members.

Quality of the contributions is often surprisingly high.

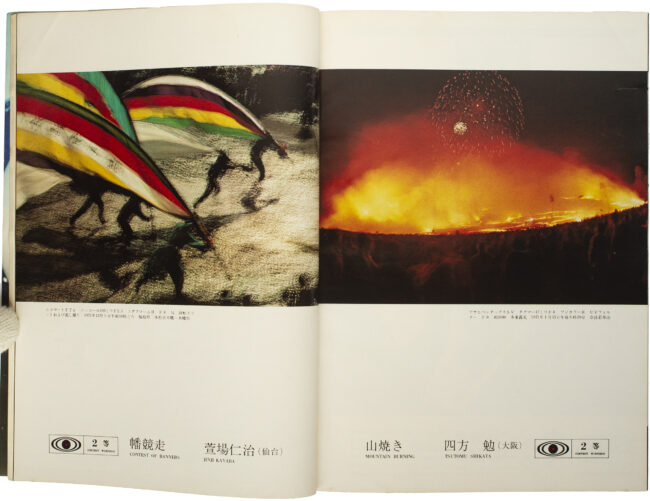

1st Prize color contest (right)

Camera Mainichi 1958 November issue.

1st Prize black and white prints (left)

Camera Mainichi 1958 November issue.

1st Prize ( spread) color contest

Asahi Camera 1959 March issue.

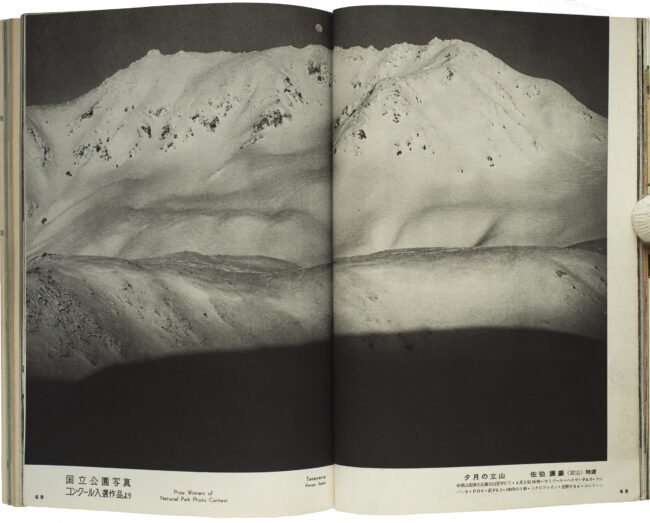

National Park contest.

Asahi Camera 1958 April Issue.

Highschool contest.

Camera Mainichi 1958 November issue.

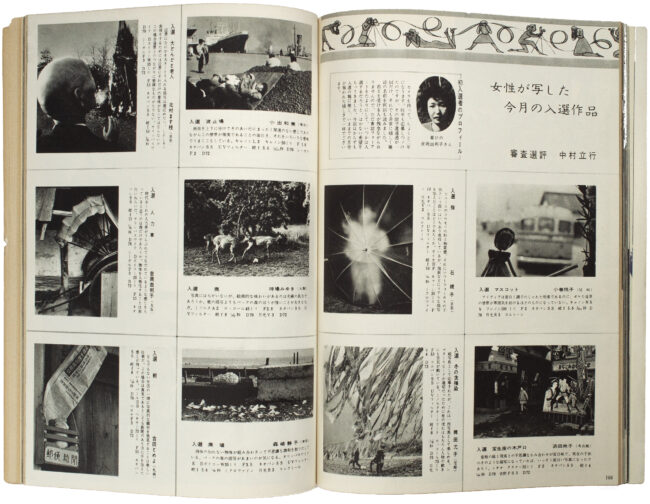

Women contest.

Photo Art 1959 April issue.

Photo Club contest.

Camera Art 1960 Januari issue

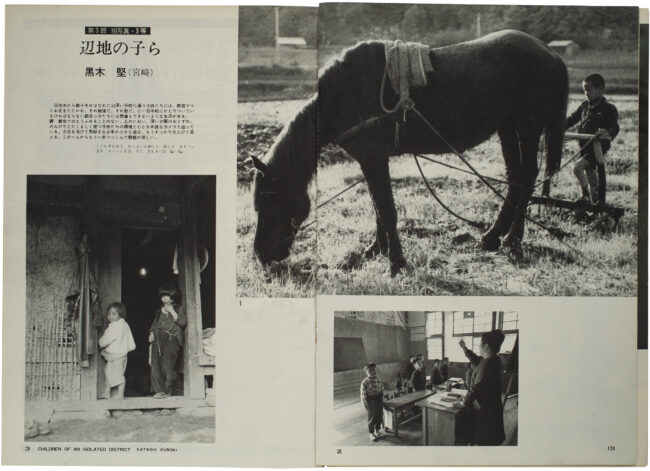

‘Children of an isolated district’. 3rd prize photo essay. Camera Mainichi 1966 September issue.

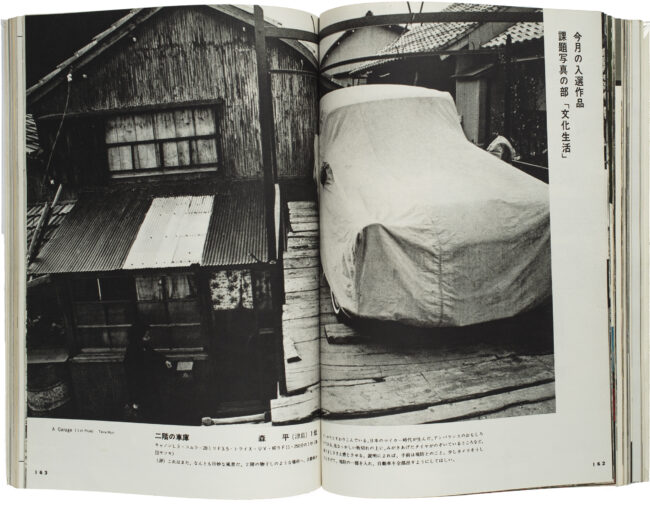

‘Second floor garage’. 1st Prize B&W large prints.

Asahi Camera 1966 December issue.

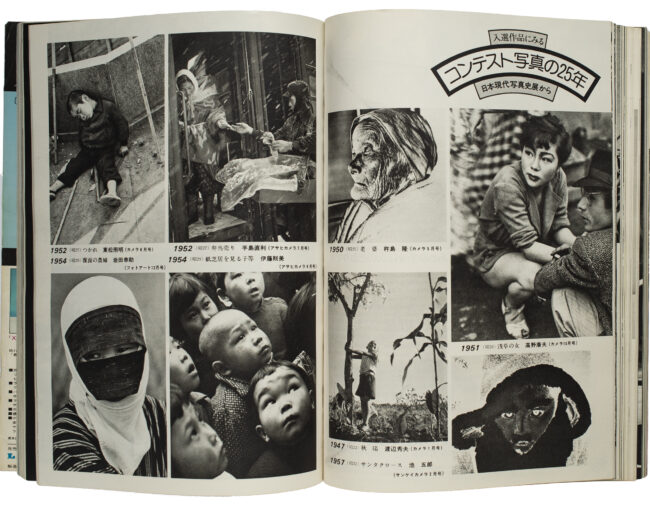

25 years of contest photography. Asahi Camera 1975 December issue.

Top left corner a contribution of Tomatsu Shomei in 1952 August issue.

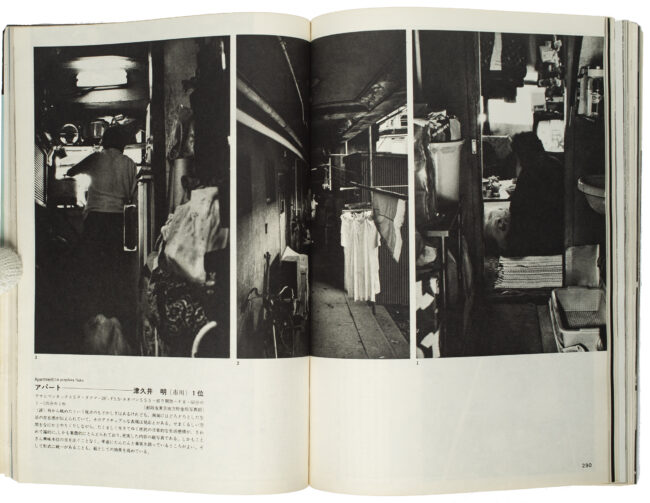

‘Appartment’. 1st Prize three-piece contest essay.

Asahi Camera 1975 December issue

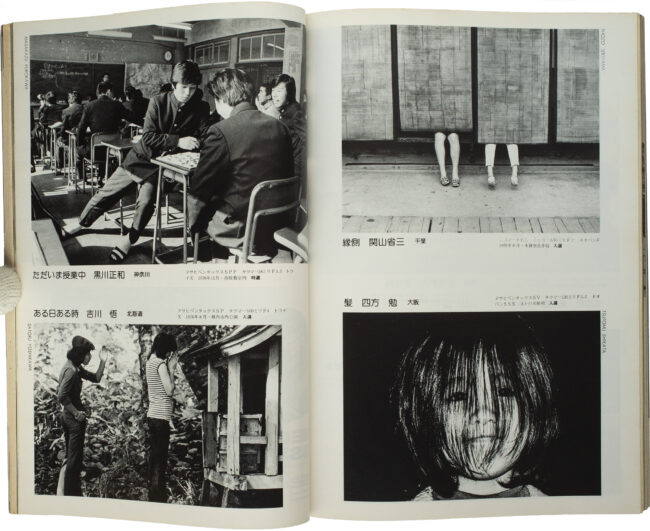

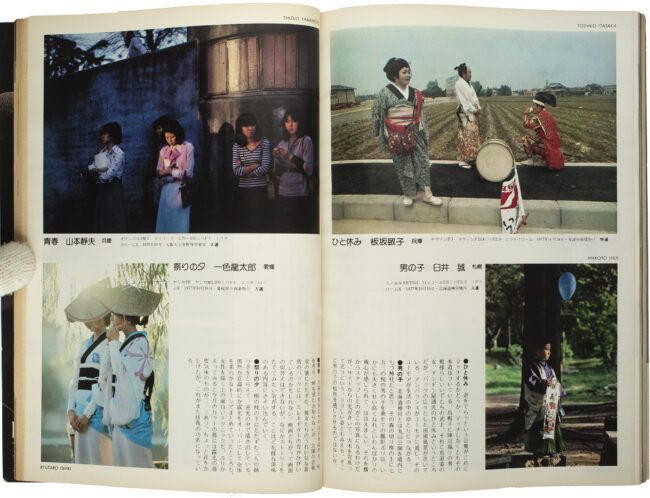

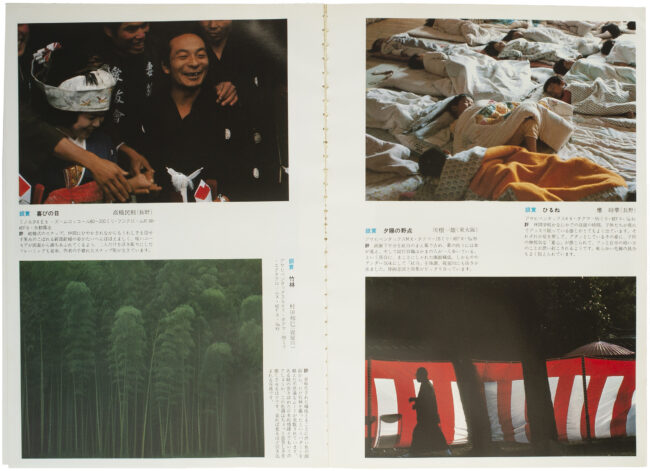

Two 2nd prize winners Color contest.

Camera Mainichi 1972 April issue

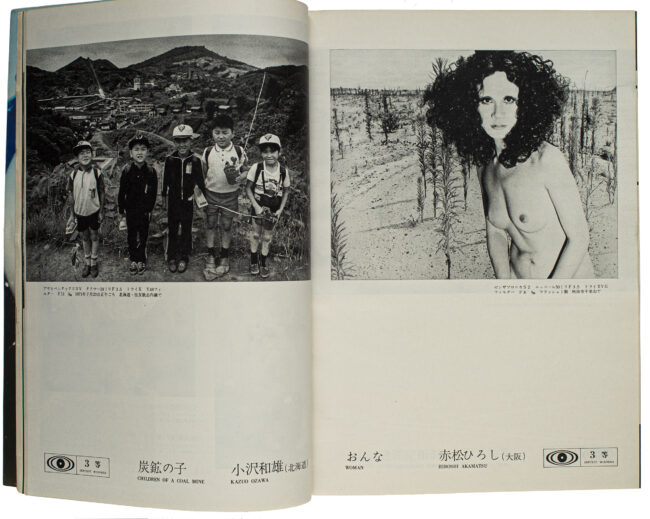

Two 3rd prize winners B&W contest

Camera Mainichi 1972 April issue

B&W contest.

Camera Mainichi 1978 February issue.

Color contest with comment.

Camera Mainichi 1978 February issue

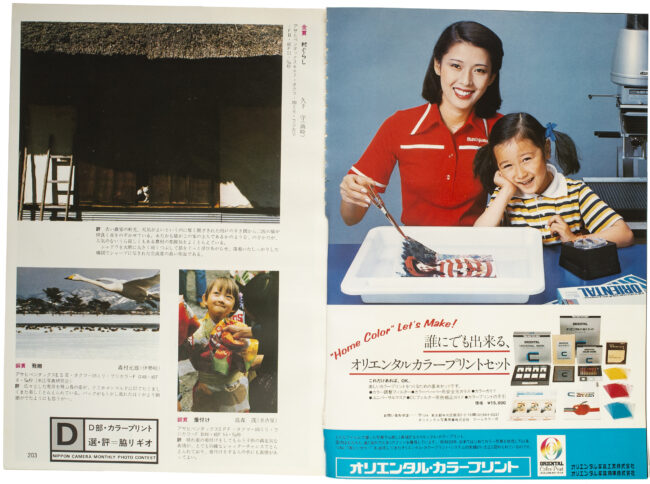

Nippon Camera Monthly Photo Contest, Part C. Color Slide. Selected and commented by Watanabe Yukichi.

Nippon Camera 1978 March issue.

Nippon Camera Monthly Photo Contest, Part C. Color Slide. Selected and commented by Watanabe Yukichi.

Nippon Camera 1978 March issue.

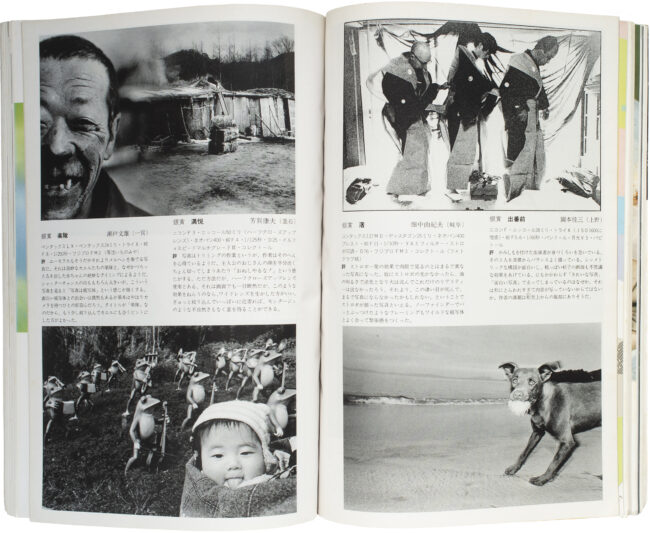

Nippon Camera Monthly Photo Contest, Part A. Large B&W print. Silver medal winners. Selection/review by Enari Tsuneo

Nippon Camera 1988 April issue.

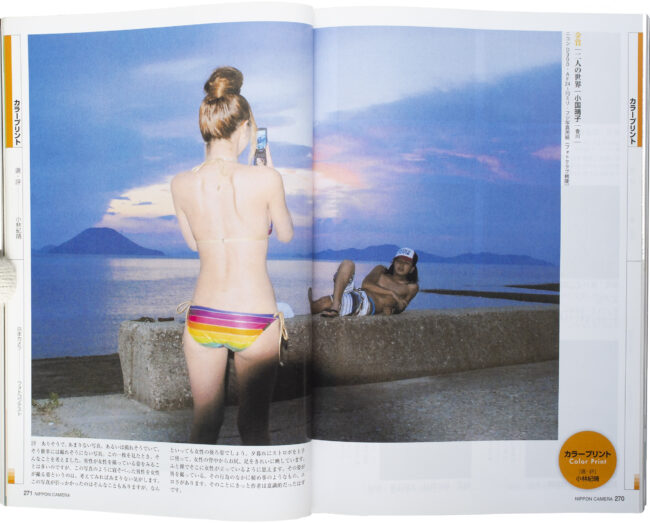

Nippon Camera Monthly Photo Contest, Color Print. Gold Award.

Evaluation by Kobayashi Noriharu.

Nippon Camera 2010 November issue.

Also the writings of photographers, such as discussions, interviews and essays about photography, played a prominent role in the magazines and created an important awareness about the content of the images for the readers.

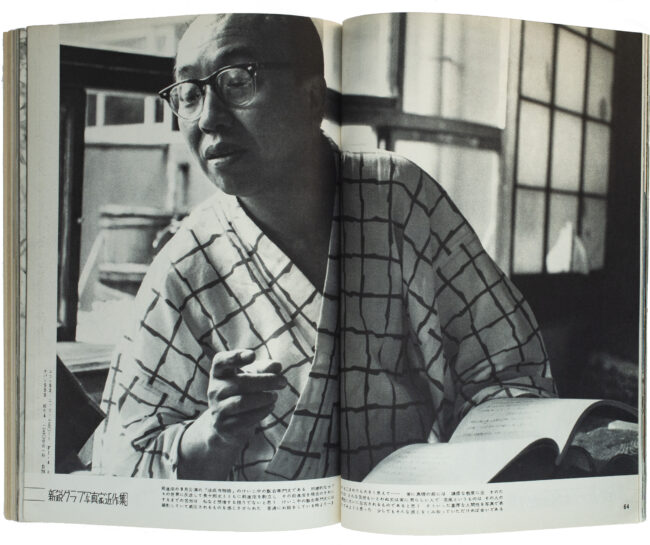

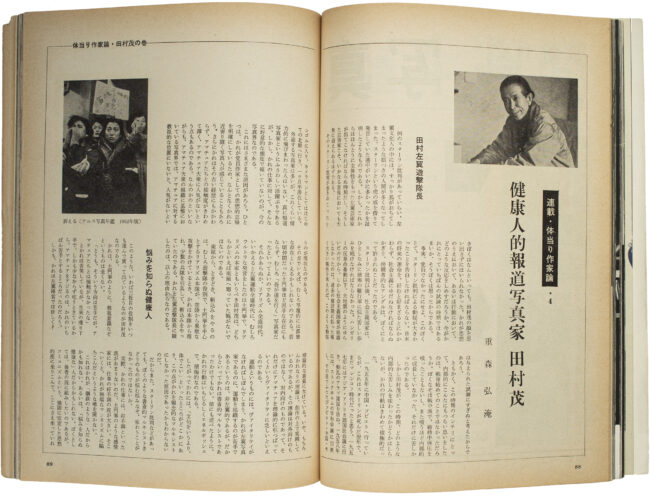

Theory of a writer; photojournalist Shiguru Tamura.

4 pages in Photo Art 1959 April issue.

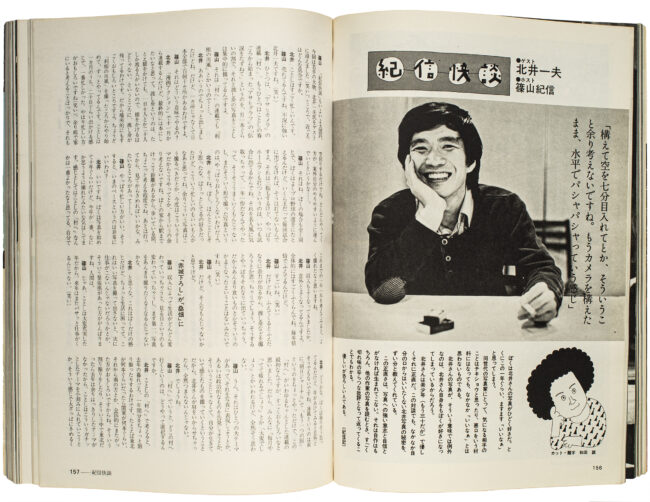

Monthly series of interviews from Shinoyama Kishin.

This month Kitai Kazuo.

6 Pages in Asahi Camera 1975 December issue.

Gliding on the skin of virtual reality. Nobuyoshi Araki’s Theory.

5 Pages in Camera Mainichi 1978 Februari issue.

Most magazines (re)started publishing in the late 1940s. Asahi Camera as being one of the oldest magazines ( 1926 - 1942 ) revived in 1949. Nippon Camera ( 1950 ), Photo Art (1949 ), Shūkan Sun News (1947 ) and Shashin no Kyōshitsu ( 1951 ).

Sankei Camera and Camera Mainichi both appear relatively late, in 1954. Sankei Camera was launched with a more dynamic editorial policy than Camera Mainichi, who published photographs from the American magazine Popular Photography under a co-publishing arrangement. This all changed in 1963 when Yamagishi Shōji became editor of the main, gravure section and made Camera Mainichi the leading magazine..

Yamagishi, a legendary jack-of-all-trades in Japanese photography, became the driving force behind Camera Mainichi in the years 1963 - 1978 as editor, and is generally regarded as the man who gave photographers such as Tomatsu Shomei, Araki Nobuyoshi, Fukase Masahisa, Shinoyama Kishin, Moriyama Daido and many others a platform and by doing so launching their careers.

Komori Takayuki played the same role as editor for Asahi Camera. Komori and Yamagishi can be seen as the founders of the golden 60s and 70s of postwar Japanese photography.

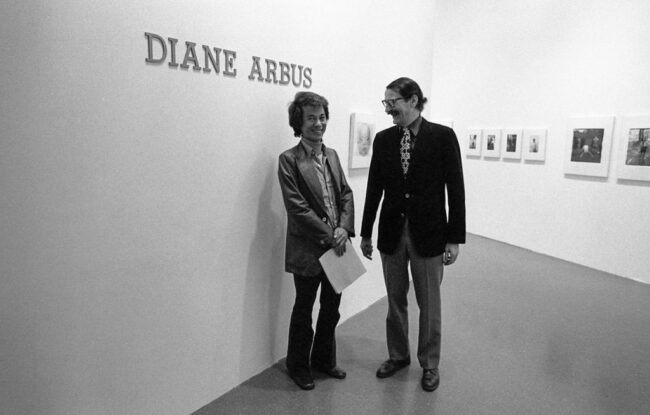

Yamagishi Shoji and John Szarkowski visiting Diane Arbus: Retrospective,

Seibu Department Store, Tokyo, 1973

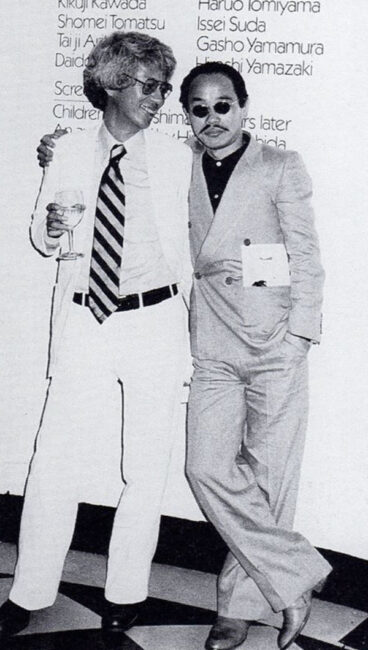

Yamagishi Shoji and Araki Nobuyoshi, opening ICP exhibition

‘Japan: A Self-Portrait’, New York 1979.

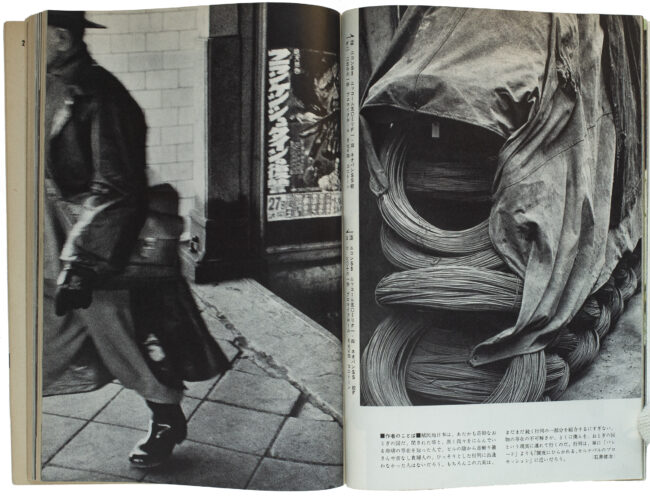

The Japanese photo magazine, like the Japanese photo book, requires a more active and involved audience, due to its layout and design: Photography as a medium to read and not just to look at as in an exhibition.

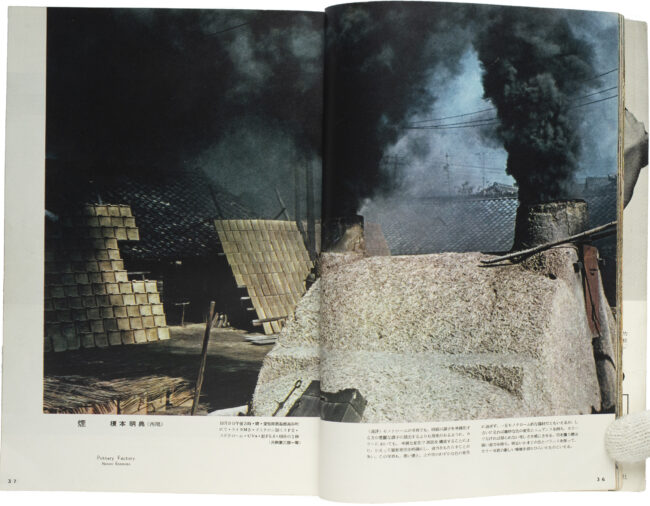

Normally, new work of photographers first appeared in the magazines.

Many photographers were given the opportunity to make series (‘rensai’), some even had a monthly contribution of 2 - 26 pages with photos over a single year.

After that often a book appeared. Magazines and books were the main platform for photographers as there were few or no exhibitions and no market for photos as collectors prints until the 1990s.

“Contemporary Japanese photographers have values which seems distinct from those of the photographers of the West. They are, for example, not particularly interested in the quality of the finished print. […] Japanese photographers have only a limited opportunity to present their original prints to the public. (Nor do they have the opportunity to sell their pictures to public or private collections.) […] Japanese photographers usually complete a project in book form, joining in series a number of photographs related by a common subject, theme, or idea. The full value or impact of such work cannot be understood if individual pictures are isolated from the series for exhibitions on the walls of a museum. To do this deprives the photographs of their intended relationship to those which preceded or followed them in the series. In addition, the photographs were originally made to be reproduced in print form, in books and magazines, and not to be displayed a part of an exhibition. It is therefore almost impossible to present a precise and objective picture of the complexities of Japanese photography in an exhibition format.”

[Yamagishi Shôji, extract from the introduction in New Japanese Photography, 1974]

The large number of photo magazines and their monthly appearance guided photographers to a large production, with little time between the shooting and the publication of the images.

This undoubtedly was an encouragement to a great deal of experimentation or searching for new ways, which (with some other factors) led to the groundbreaking and radical photography of the 1960’s.

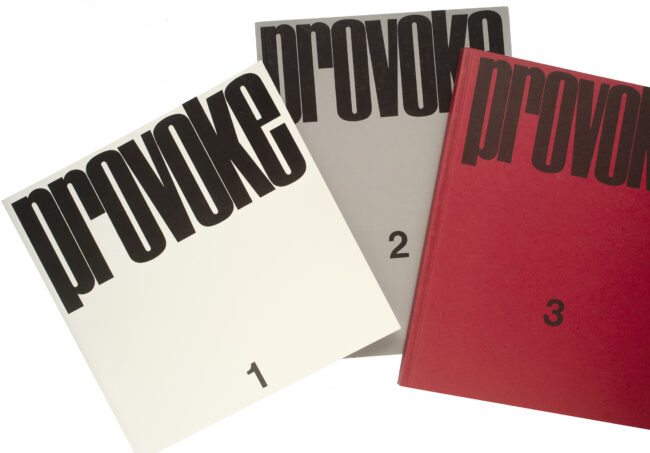

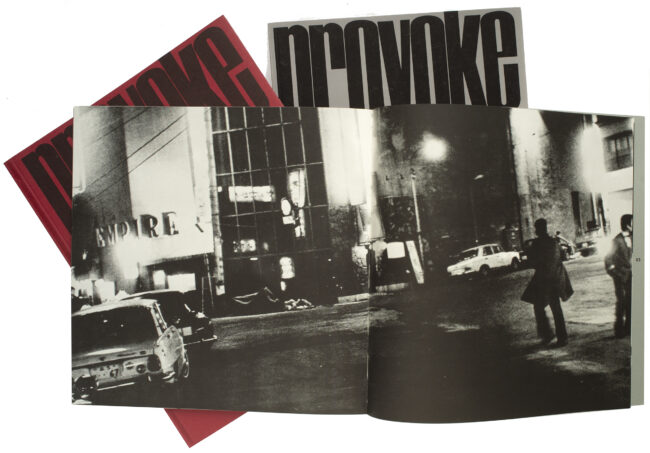

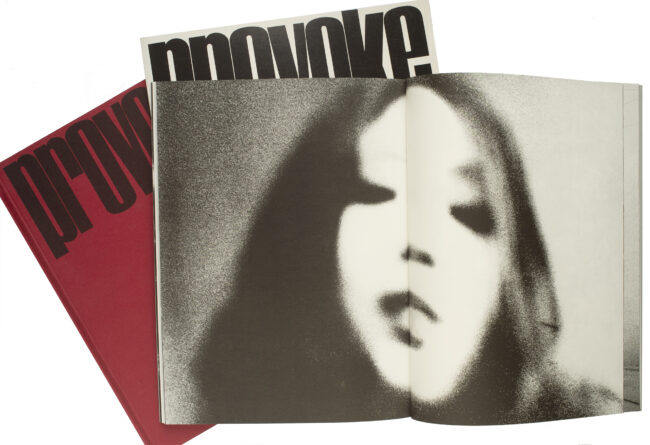

An exponent of this was the magazine Provoke (1968 - 1969, 3 issues, each volume only 1000 printed copies )

With its avant-garde mix of photography, experimental poetry as well as philosophical, political and critical essays, gives Provoke’s three issues nowadays a cult status, but it got marginal attention at the time. Provoke was published in Tokyo by the photographer and writer Nakahira Takuma, the art critic Taki Koji, the poet Okada Takahiko and the photographers Takanashi Yukata and Moriyama Daido ( who joined the group from the second issue).

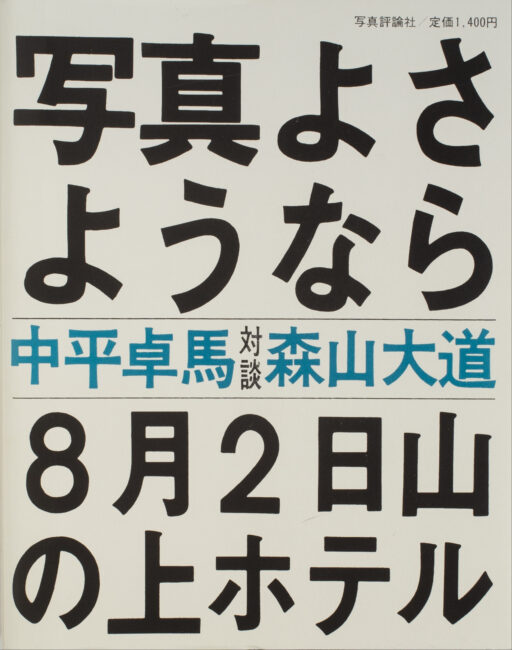

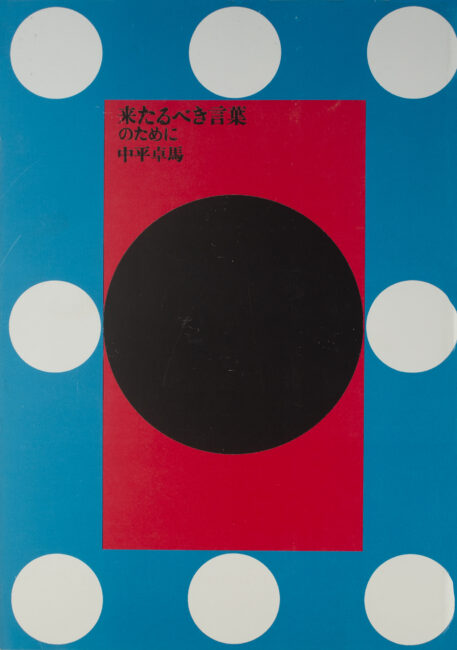

Investigating the relationship between photography and text and suggesting new ways for photography to depict Japanese society, the magazine was an artistic and philosophical manifesto, responding to the upheavals of the late sixties. The participating photographers searched for a radically new photographic language, as is reflected in their booktitles like Moriyama’s “Bye, Bye Photography“ ( Sashin yo Sayonara ) , and Nakahira’s “For a Language to Come” (Kitarubeki Kotoba no Tame ni); publications that were turning points in postwar Japanese photography. The group disbanded in 1970 with the publication of a book called: “First Discard the World of Pseudo-certainty”, ( “Mazu Tashikarashisa no Sekai wo Sutero: also named Provoke 4 & 5 ) in which they reviewed their activities.

Moriyama Daido; Bye, Bye Photography. 1972

Nakahira Takuma; For a Language to Come. 1970

Nakahira Takuma, Taki Koji, Okada Takahiko, Amano Michie, Moriyama Daido, Takanashi Yutaka; Provoke 4 & 5. 1970

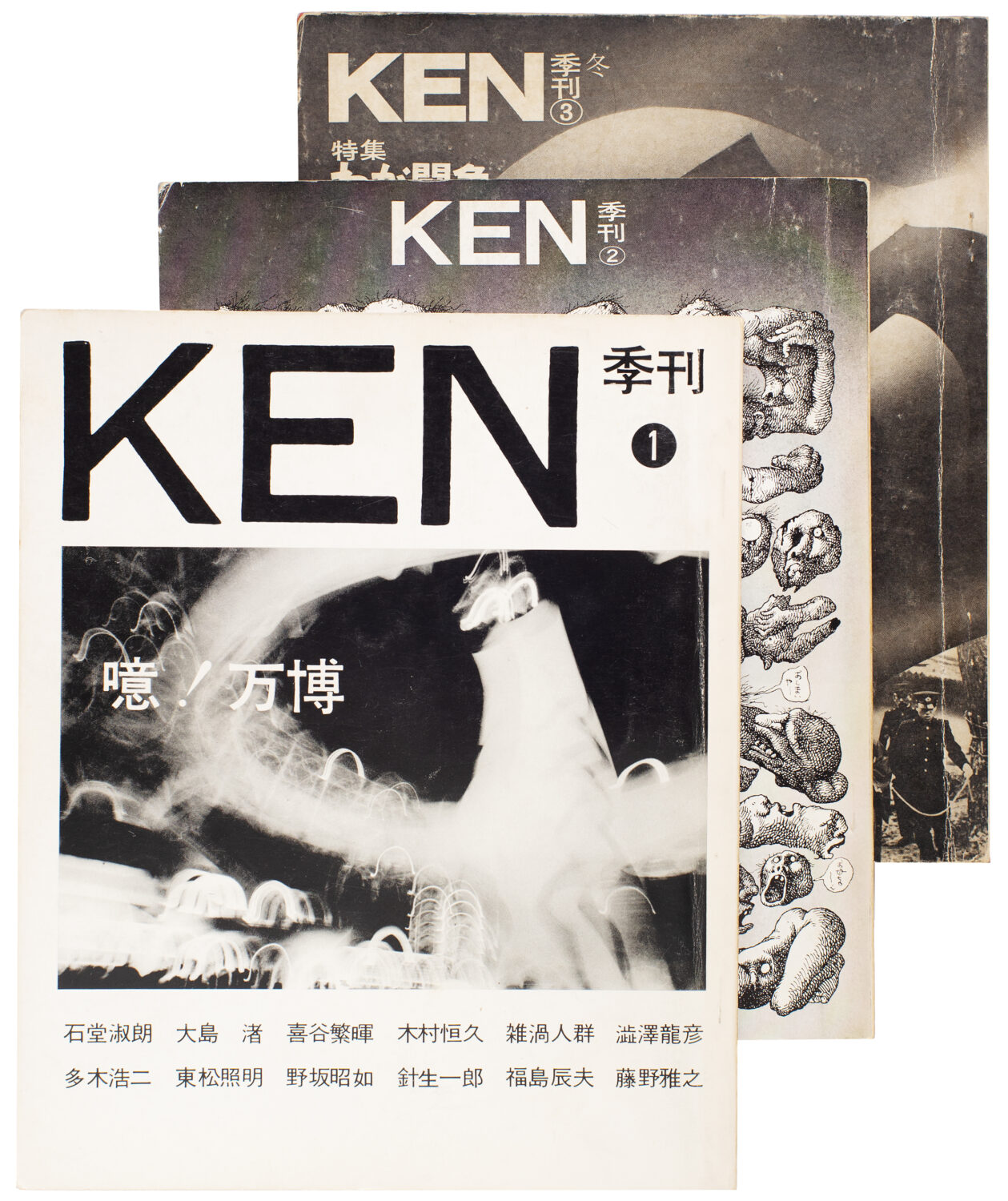

In the same period more short lived, but important and radical magazines appeared, like KEN, 3 volumes 1970-1971. Ken was published by Shaken, founded by Tomatsu Shomei.

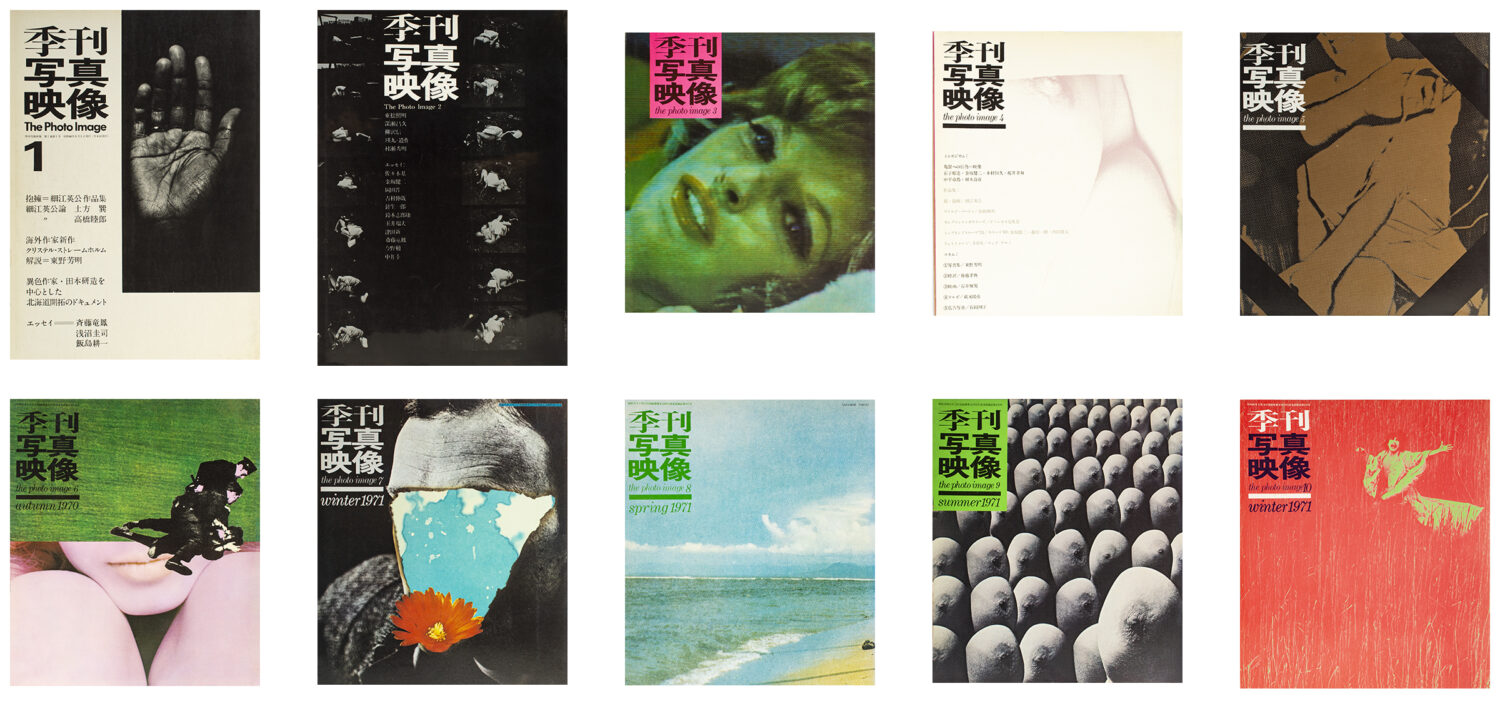

And ‘The Photo Image’ ( Kikan Shashin Eizo ) , 10 volumes, 1969-1971. Edited by Kuwahara Kineo, works by Hosoe Eikoh, Shinoyama Kishin, Takanashi Yutaka, Fukase Masahisa, Tomatsu Shomei, Nakahira Takuma, Naito Masatoshi, Kawada Kikuji, Araki Nobuyoshi, Ishioka Eikoh, Yokoo Tadanori, Sato Akira etc.

Aggressive layout with a mix of styles, papers and printing techniques.

The content of the popular JPN magazines can be roughly divided into three categories:

-The work of photographers; professionals and amateurs ( with their contributions in the monthly contests )

-Learning and instructional topics.

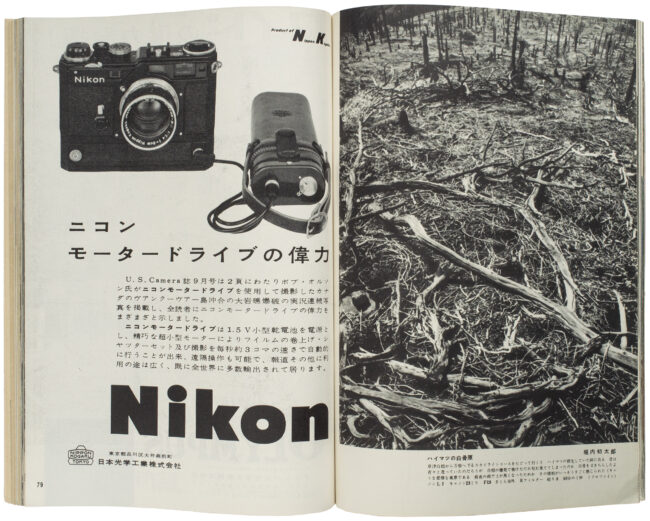

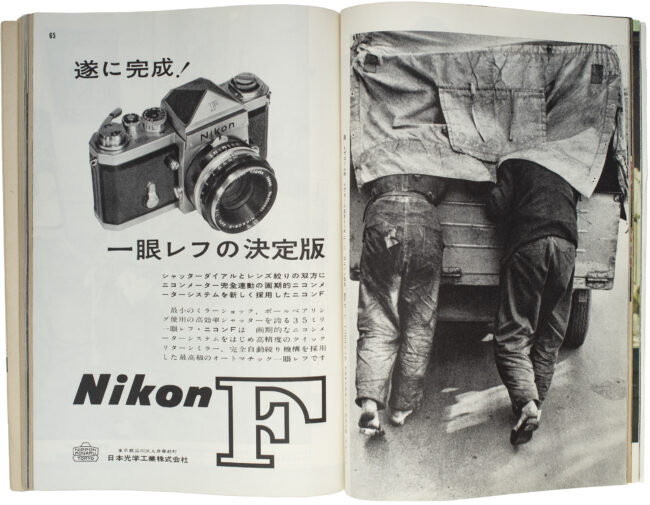

-Advertisements for cameras and other photographic equipment, like films, darkroom equipment etc.

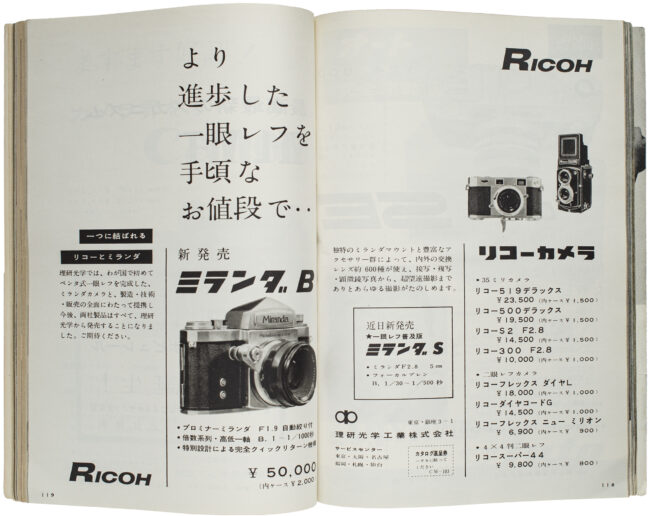

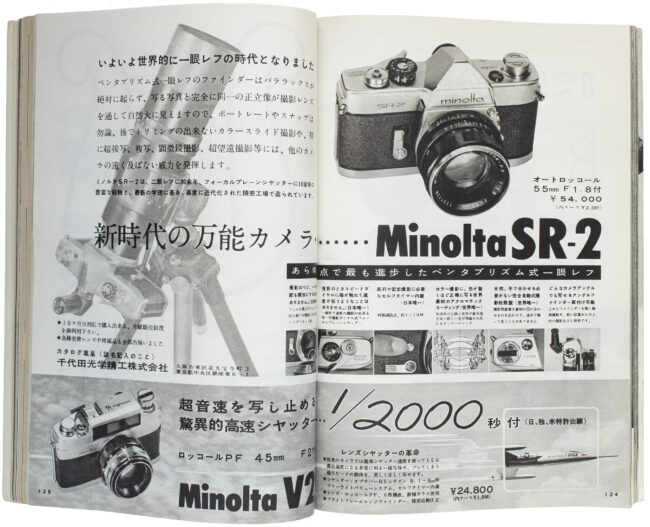

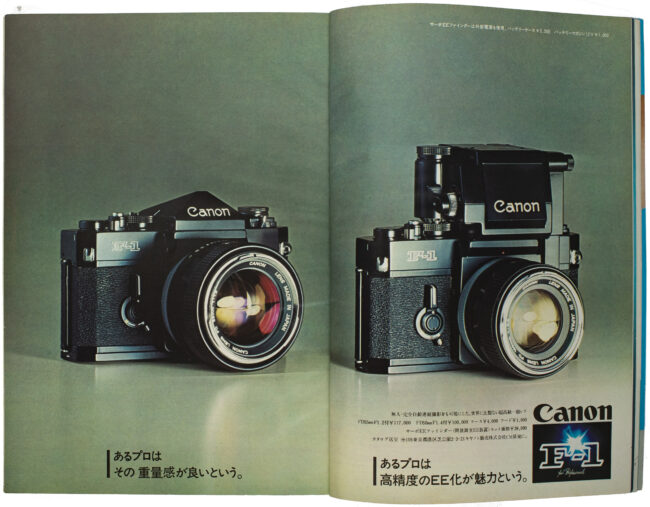

The advertisement section was a major source of income for the magazines.

The Asahi Camera April 1958 issue counts 77 pages of ads, on a total of 250 pages. The Asahi Camera December 1966 issue counts 100 pages of ads on a total of 300 pages. The Asahi Camera December 1975 issue had 179 pages of ads on a total of 384 pages.

Looking back they give a nice view on how camera advertisement evolved through the years, but above all they give a good insight in the development of the Japanese camera industry. They advertised beautifully designed and technically advanced cameras, that, with a very competitive price tag soon outstripped the European camera manufacturers. At the end of 1960s the Japanese 35 mm camera was, and still is, the standard tool for the professional as well as the amateur photographer.

During the 1980s the focus of the ads shifted to only the amateur consumers.

The magazines of ‘the radical movement’ had hardly any advertisements. Provoke and KEN had none, Kikan Shashin Eizo just a few.

1958 Camera Mainichi

1959 Sankei Camera

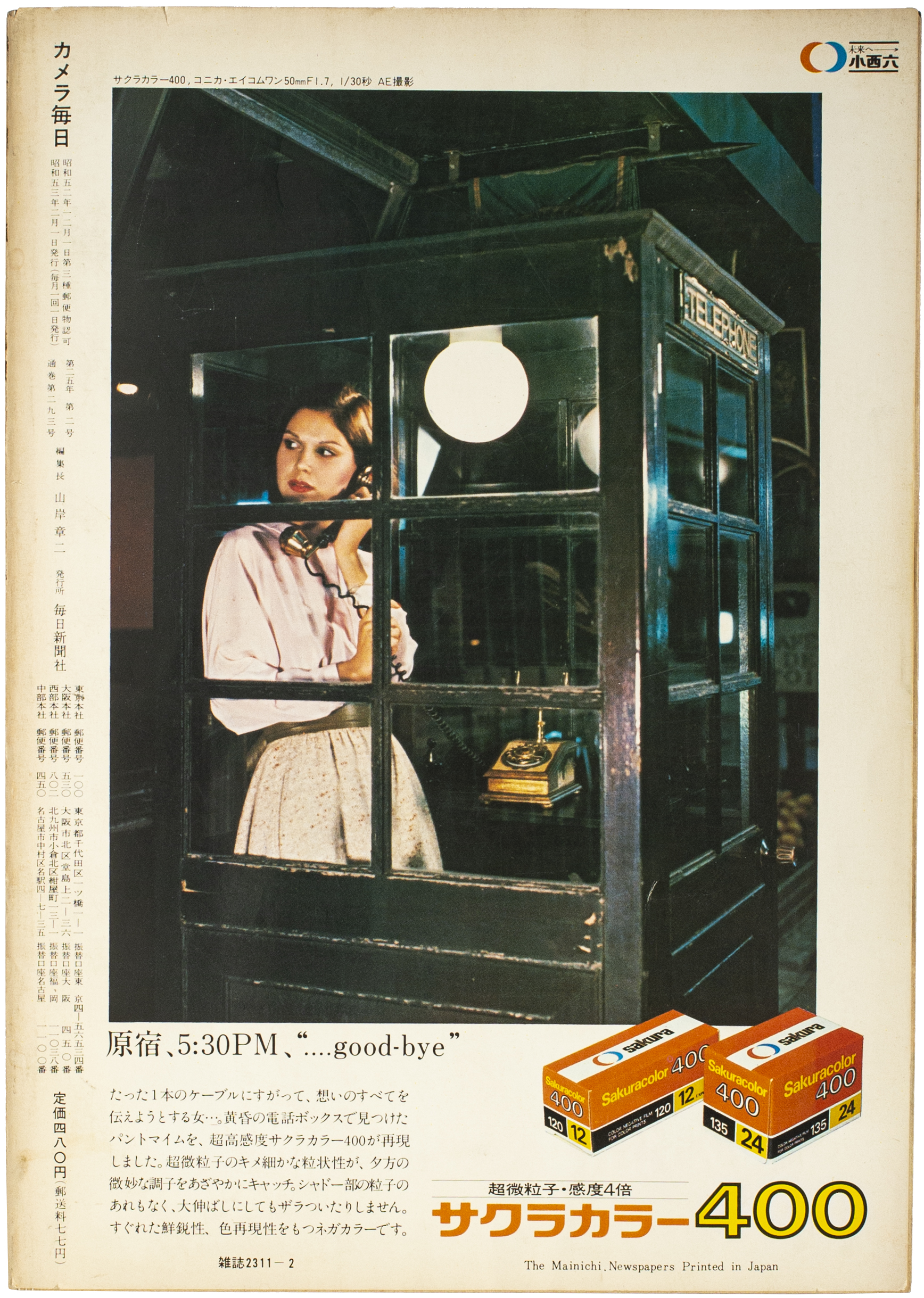

1978 Camera Mainichi

1959 Asahi Camera

1966 Asahi Camera

1972 Camera Mainichi

1959 Asahi Camera

1977 Camera Mainichi

1972 Camera Mainichi

1958 Camera Mainichi

1975 Asahi Camera

1978 Nippon Camera

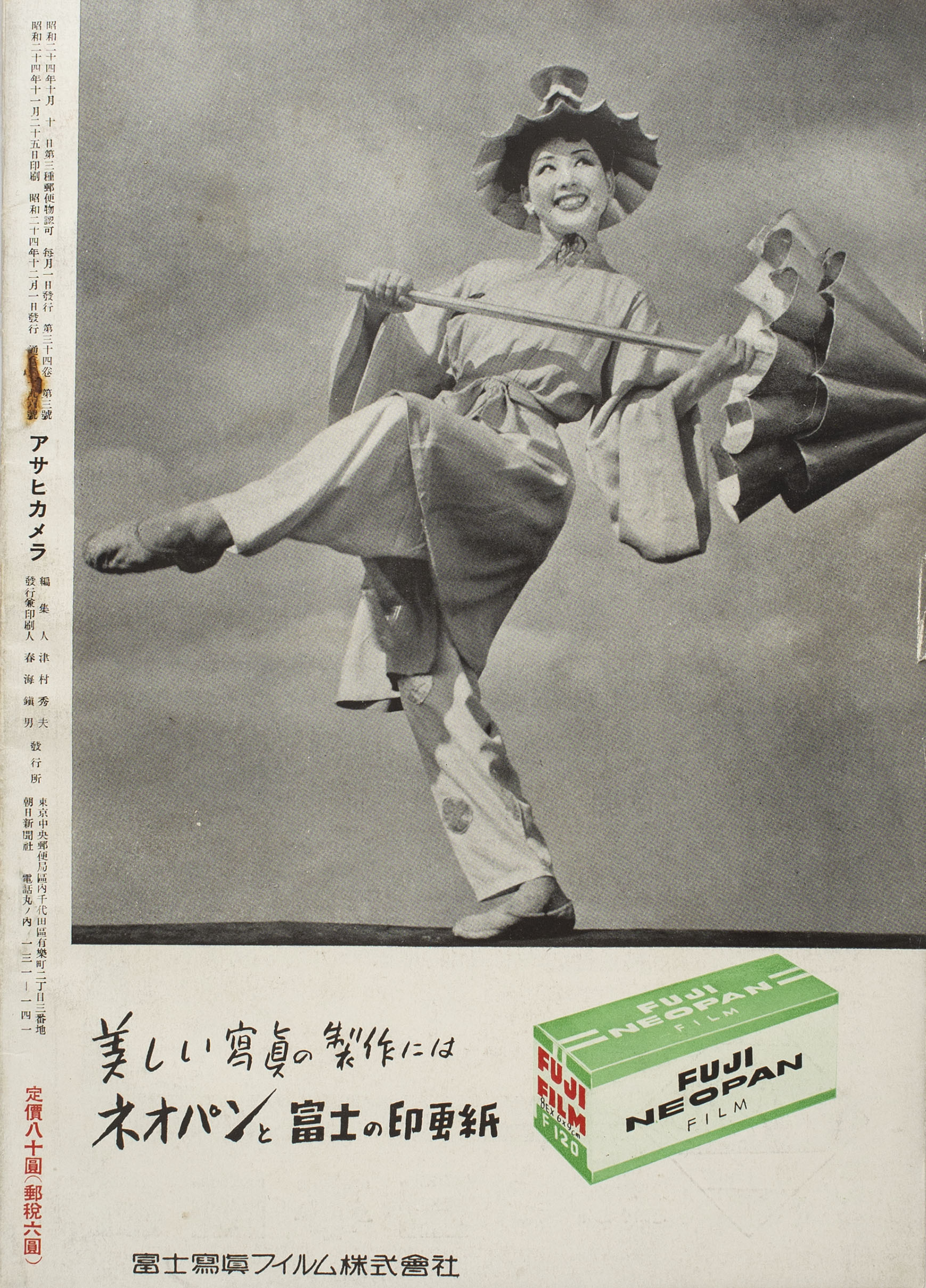

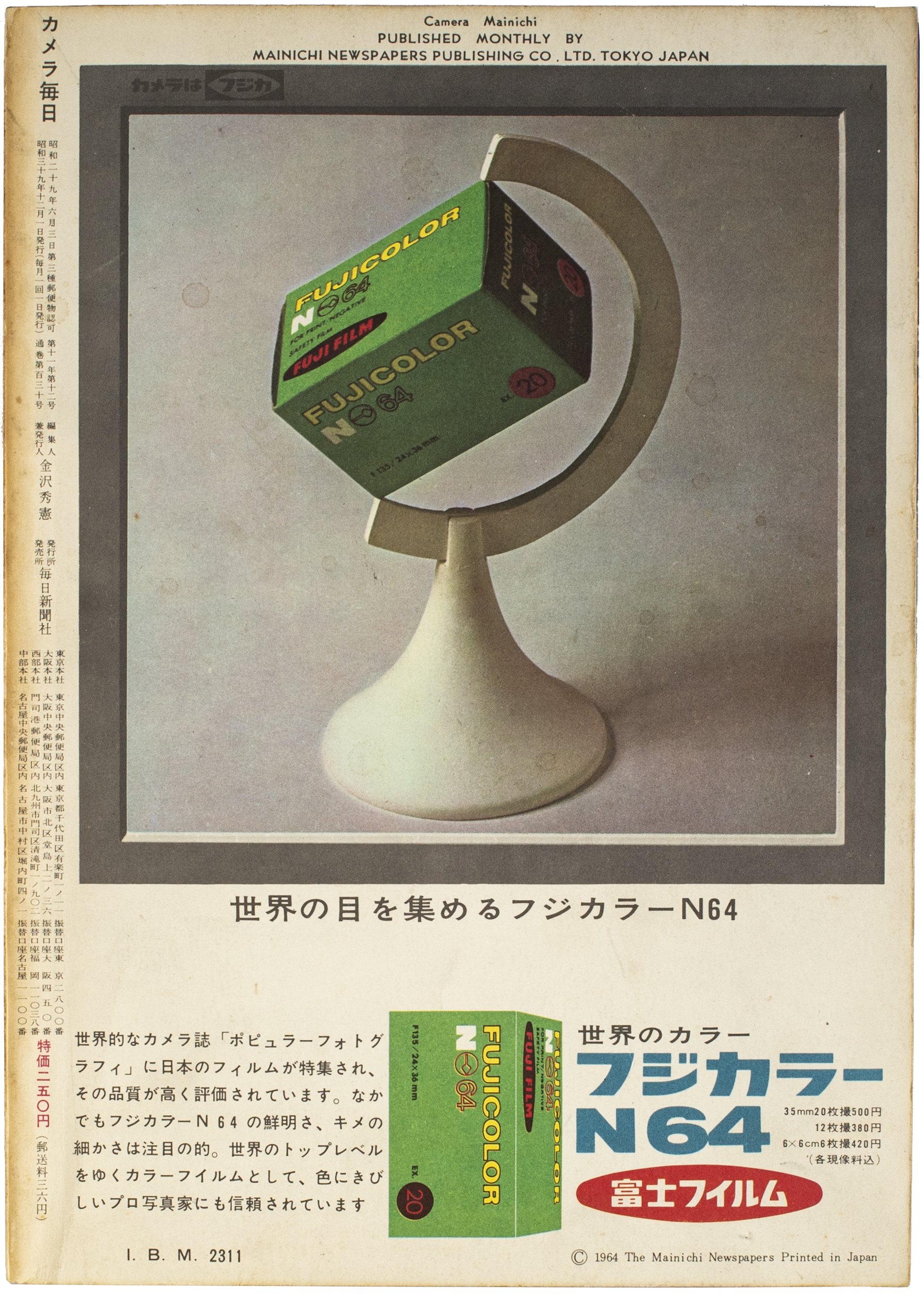

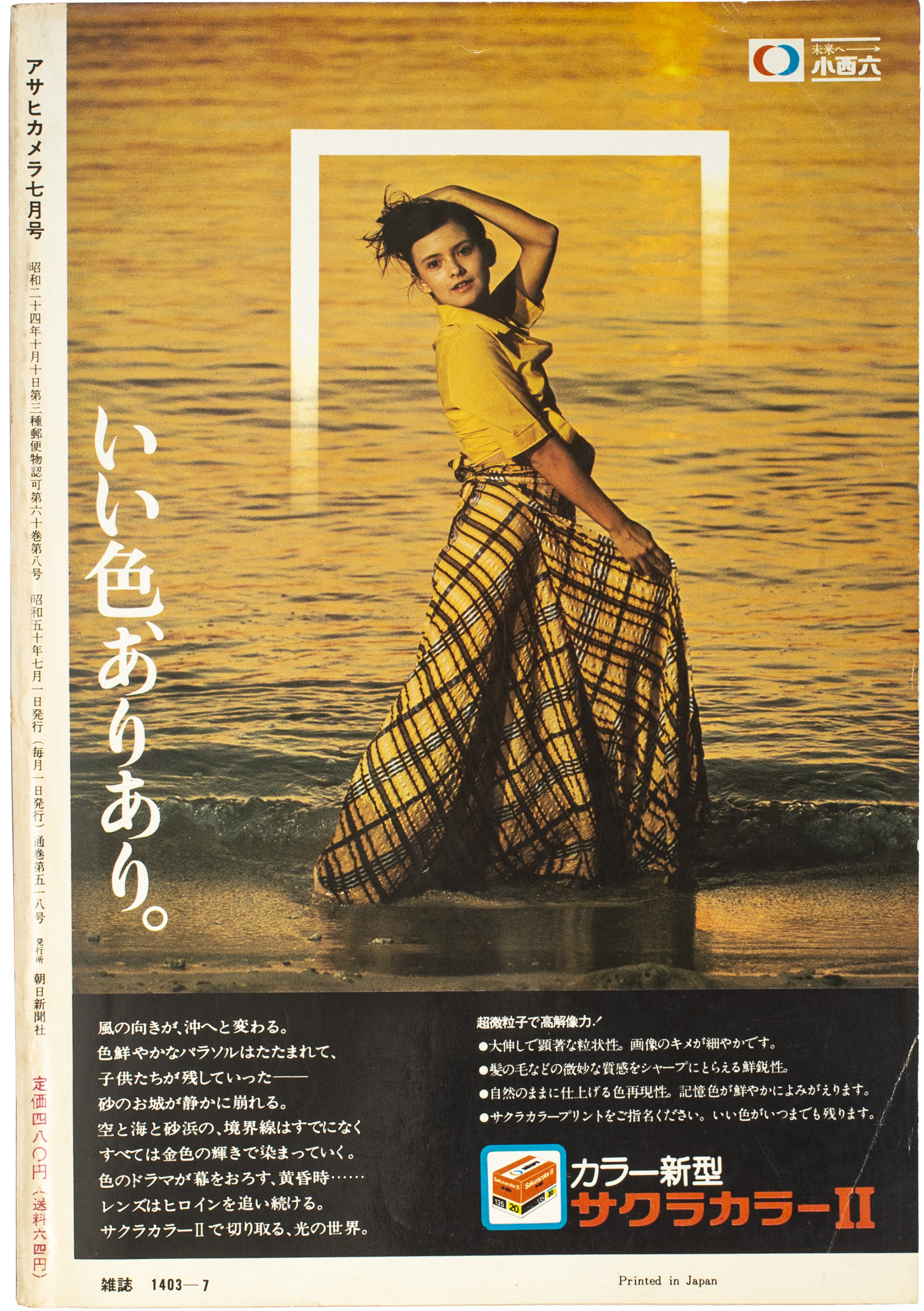

The back covers seemed exclusively for the film manufacters, like Fuji and Sakura. In the 1950s the back covers were the only ads in color.

1949 Asahi Camera

1958 Camera Mainichi

1964 Camera Mainichi

1966 Asahi Camera

1975 Asahi Camera

1978 Camera Mainichi

In the 1980s and 1990s things were changing.

‘Internationalization and growing individual independence changed the climate for making art, and it also altered the context for photography. Since the 1980s, photography has become widely accepted as an art medium by the public around the world; as with other countries, as in Japan this has lead to a strengthening and professionalization of the infrastructure for the production , distribution and exhibition of photographs. Beyond this, with the arrival of national affluence and increasing globalization in Japan, the photography network of local circles and their casual, personal contacts through clubs, galleries and magazines could no longer serve the larger needs of the field and its practitioners, historians, and collectors, not to mention a public that was eager to see and know more.’

( Dana Friis-Hasen; Internationalization, Individualism, and the Institutionalization of Photography * )

The golden years of the Japanese photo magazine slowly came to an end.

From the leading magazines, Camera Mainichi ceased publication in April 1985. Asahi Camera published until July 2020, when it was discontinued due to declining circulation. Nippon Camera, as longest living of the popular photo magazines, suspended their publication after the May 2021 issue.

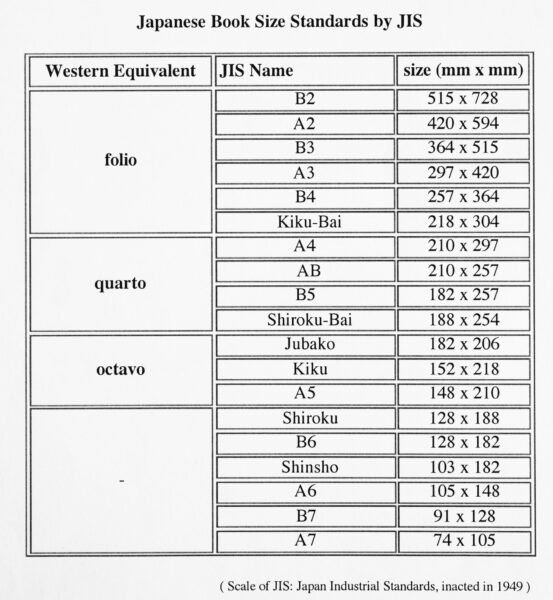

Finally, some small general notes on the JPN magazines;

Japanese names appear on this website in Japanese order, that is, with family name first.

Text in articles, interviews and gear talk are mostly from top to bottom ( tategaki ) The reader progresses from the upper right corner of a page to its bottom left corner.

Captions and advertisements are mainly written in horizontal ( yokogaki )

Like Japanese books and newspapers, magazines usually had left opening. So the the right-hand page precedes the left-hand page, which often means that the first image and title of an essay starts on the left page.

Left opening

*( Essay from The History of Japanese Photography. 2003, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)

The chapter ‘Major Photography Magazines’ in ‘The History of Japanese Photography’ by Anne Wilkes Tucker ( 2003 Museum of Fine Arts, Houston) was very helpful.

The ultimate book on this subject: 'Japanese Photography Magazines 1880s - 1980s' : Kaneko Ryūchi, Toda Masako and Ivan Vartanian. Goliga Books 2022.

https://goliga.com/japanese-photography-magazines-1880s-to-1980s

The Magazines.

A selection of Japanese photo magazines, and other magazines where photography played an important role, with images of the covers, selected works of photographers, and a summary of the content of each issue, can be found here.

They appear in chronological order, on date of first publication.

Asahi Graph

Asahi Camera

Sashin Salon

Photo Art

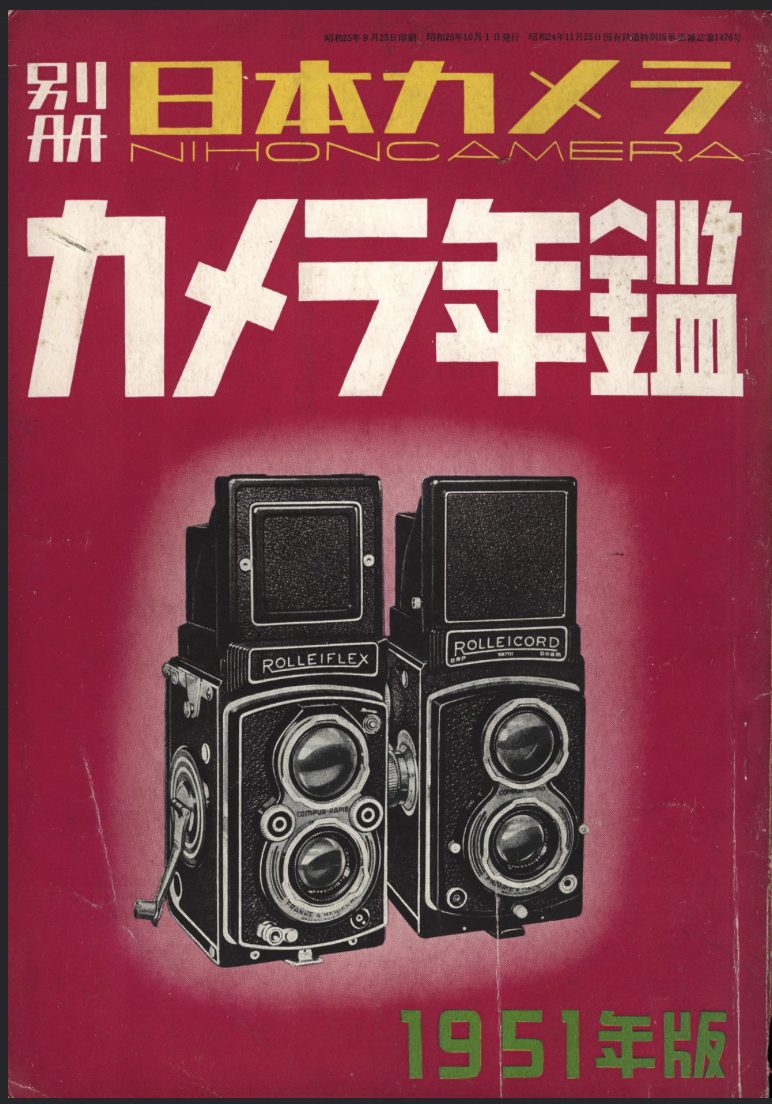

Nippon Camera

Shashin no Kyōshitsu

Sankei Camera

Camera Mainichi

Rokkor

Eiga Hihyo

Asahi Journal

Camera Art

Taiyo

Camera Jidai

Graphication

Provoke

Kikan Shashin

KEN

An An

Geijutsu Seikatsu

Workshop

Camera Works Tokyo

Shagaku

On the Scene

Brutus

Shashin Sōchi

Shashin Jidai

Focus

Photo Japon

Eifel Tower

Photo wave

Deja Vu

Main

Photografica

Asphalt

IMA