Camera Mainichi カメラ毎日

June 1954 - April 1985

Monthly

Founding Publisher: Mainichi Shimbunsha ( Tokyo)

Founding Editor: Inoue Sōjirō

B5 size, approx. 18 x 26 cm

Camera Mainichi, with its newspaper publisher Mainichi Shimbunsha, can be regarded as a ‘newspaper-based camera magazine’ .

As Ivan Vartanian writes in his introduction in Japanese Photography Magazines 1880s-1980s* ; ‘mainstream photography magazines in the postwar era fell into either one of two categories: newspaper-based camera magazines (Camera Mainichi, Asahi Camera and Sankei Camera) and publishers specializing in camera magazines ( Camera, Nippon Camera, Photo Art )

With photo contests, news and reviews of camera equipment, Camera Mainichi was also aiming at the amateur photographers, just as its fellow camera magazines, but with its relative late introduction on the market, they tried to give the magazine a small twist.

At it’s launch, Robert Capa, a star in Japan thanks to his work in ‘Life’, was invited and do the promotional campaign, which lead to a long standing contract with the international photographic agency Magnum, featuring the work of their photographers, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson.

In that perspective, more than the camera-based magazines, Camera Mainichi leaned toward reportage and documentary photography.

In those early years, Camera Mainichi had also a co-publishing arrangement with the American magazine ‘Popular Photography’.

A big change came in 1963, when Kanazawa Yusuke became the editor-in-chief and made Yamagishi Shōji responsible for the gravure pages in the first section of the magazine and so created space for first-rate and unconventional photography, launching the carriers of a new generation of young photographers.

Yamagishi's unconventional approach made Camera Mainichi the leading magazine.

Yamagishi had joined the newspaper Mainichi Shimbun in 1950 as a cameraman, and then moved to Camera Mainichi as an editor in 1958. Kishi Tetsuo was the editor-in-chief and in charge for the main section, selecting the established photographers as Domon Ken, while Yamagishi Shōji did the editing of the not well known photographers.

After Yamagishi left in 1978, the magazine lost his innovative character. Sales declined and with Nishii Kazuo as the last editor, it ceased publication in April 1985

Along with Asahi Camera and Nippon Camera, Camera Mainichi became known as ‘the big three’.

* Japanese Photography Magazines, 1880s - 1980s

by Kaneko Ryūichi, Toda Masako, Ivan Vartanian

.

Goliga books 2022

.

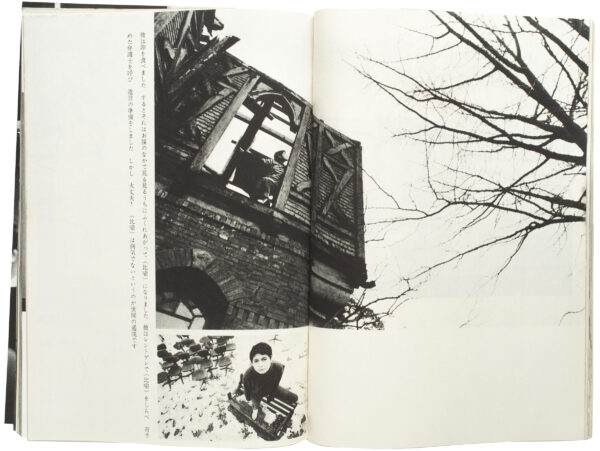

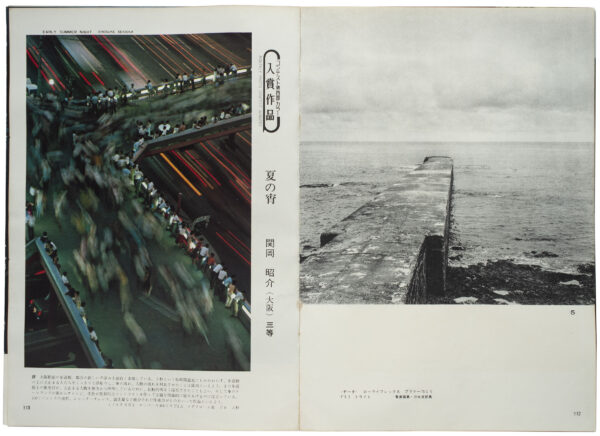

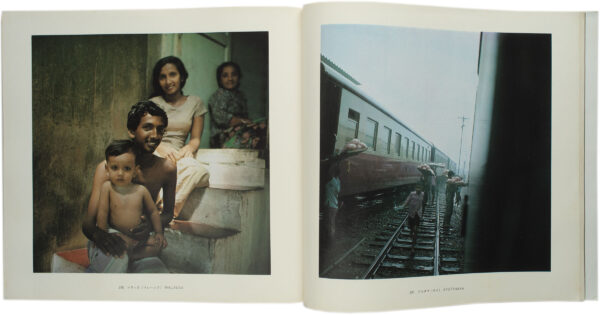

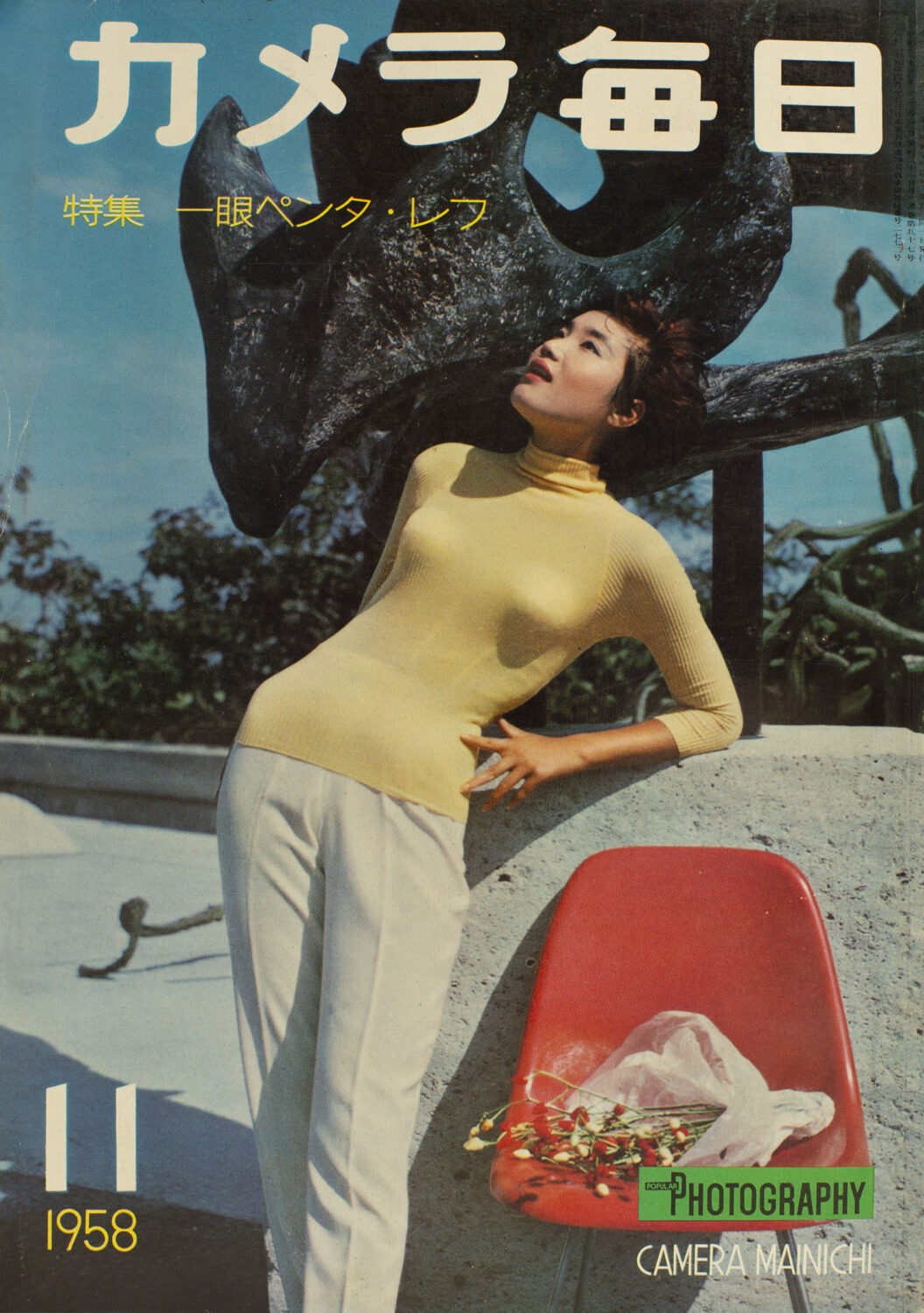

Camera Mainichi 11-1958

Editor: Kishi Tetsuo

Cover: Takamasa Inamura

218 pages, gravure printing

Selection of content:

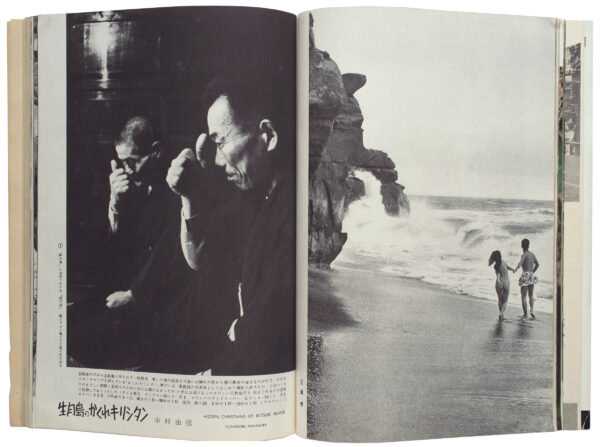

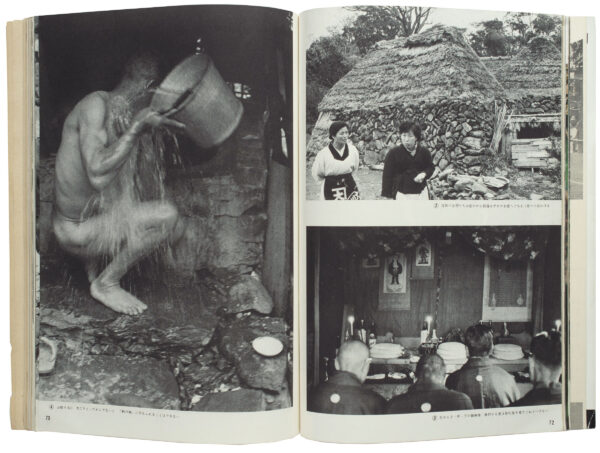

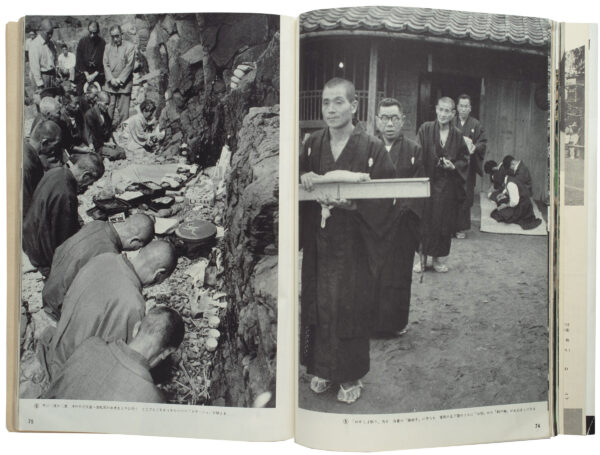

Color Feature: contribution by Fukuhara Kenji, Ueda Shōji, Abe Nobuya. 3 pages color / Faces of nations, 4 pages color / Midday on the farm, Narahara Ikko, 2 pages color / Forest and nude, Hanada Toshio 4 pages color / Fuji contest first price / Portrait, 2 pages color / 1958 in color, Ishi Kiyoshi, color foldout page / Edouard Boubat, 8 pages b&w / Monthly photo contest winners, 7 pages b&w / Expression of Japan, Suzuki Shigeo, b&w foldout page /Pilot farm, Matugi Fujio, 4 pages b&w / Romance at the seashore, Nakamura Tauyuki, 4 pages b&w / Hidden Christians of Ikitsuki Island, Nakamura Yoshinobu, 5 pages b&w / Collection of works by the single lens reflexcamera, 11 pages b&w / Monthly photo contest winners part 2, 20 pages b&w / Special feature single lens reflexcamera, roundtable discussion, using a reflexcamera, list of domestic produces SLR camera’s and lenses, list overseas SLR camera’s, 13 pages / November contest, 2 pages color / Explore autumn colors, 6 pages color / How to take still-life photos, 4 pages b&w / 8 mm cine guide, 3 pages / new products, 7 pages / exhibition news /

Camera Mainichi 11-1958

Editor: Kishi Tetsuo

Cover: Takamasa Inamura

218 pages, gravure printing

Selection of content:

Color Feature: contribution by Fukuhara Kenji, Ueda Shōji, Abe Nobuya. 3 pages color / Faces of nations, 4 pages color / Midday on the farm, Narahara Ikko, 2 pages color / Forest and nude, Hanada Toshio 4 pages color / Fuji contest first price / Portrait, 2 pages color / 1958 in color, Ishi Kiyoshi, color foldout page / Edouard Boubat, 8 pages b&w / Monthly photo contest winners, 7 pages b&w / Expression of Japan, Suzuki Shigeo, b&w foldout page /Pilot farm, Matugi Fujio, 4 pages b&w / Romance at the seashore, Nakamura Tauyuki, 4 pages b&w / Hidden Christians of Ikitsuki Island, Nakamura Yoshinobu, 5 pages b&w / Collection of works by the single lens reflexcamera, 11 pages b&w / Monthly photo contest winners part 2, 20 pages b&w / Special feature single lens reflexcamera, roundtable discussion, using a reflexcamera, list of domestic produces SLR camera’s and lenses, list overseas SLR camera’s, 13 pages / November contest, 2 pages color / Explore autumn colors, 6 pages color / How to take still-life photos, 4 pages b&w / 8 mm cine guide, 3 pages / new products, 7 pages / exhibition news /

.

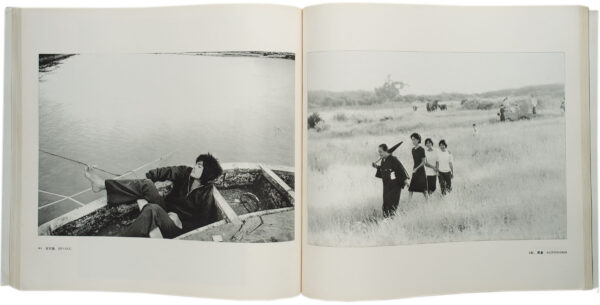

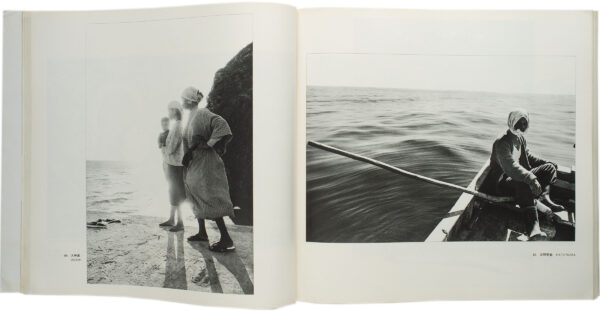

Nakamura Yoshinobu ; Hidden Christians of Ikitsuki Island 5 pages

'An hour and a half away from Hirado in Nagasaki prefecture on a cruise ship, the isolated island of Ikitsuki island in the east china sea has been home to a group of ‘hidden christians’ who have been worshipping Santa Maria for 30 years escaping the oppression of the Tokukawa shogunate. As a photographer I was allowed to photograph pagans for the first time, but due to strict restrictions and guards, i was unable to take enough pictures, but i did my best to document.'

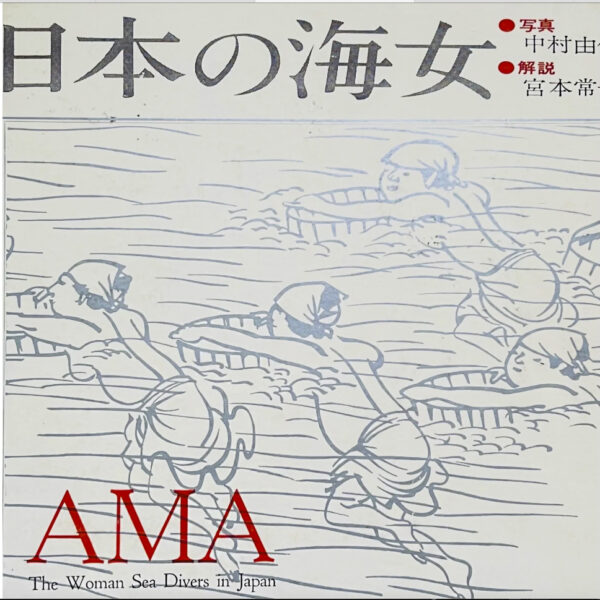

Born in Naoshima, Kagawa in 1925, Nakamura's father was one of the last Amimotos in Naoshima. He grew up looking at the Seto Inland Sea from an early age and continued to take amateur photography even after working at the Mitsubishi Smelter and studied under Yoichi Midorikawa, a leading photographer of the Seto Inland Sea. After passing the age of 30, he became a professional photographer and started "Travel in the Seto Inland Sea" and "Citizens of the Seto", depicting the local climate and culture through photographs.

His "Ama" has left a meaningful work that conveys the fading Japanese folk.

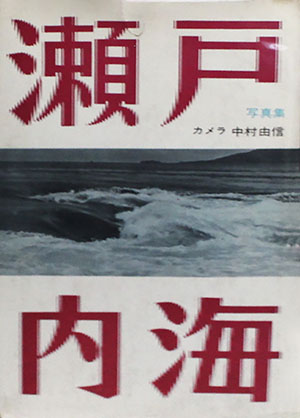

Seto Island Sea is the first personal work published in 1959.

Seto Island Sea 瀬戸内海

Kadokawa Shoten, 1959, hardcover, 87 pages

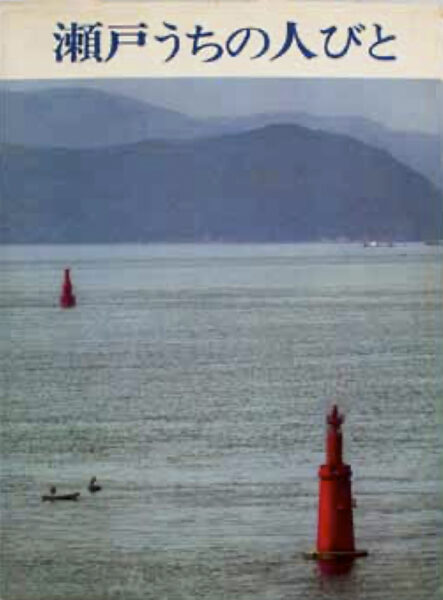

People of Seto 瀬戸うちの人びと

Shakai Shiso Shaken, 1965, Soft cover & slipcase,

29,8 x 22,8 cm, 193 pages.

Ama Woman Sea Divers in Japan 日本の海女

Tokyo Chunichi Shimbun, 1962, 192 pages - 26 x 27 cm

.

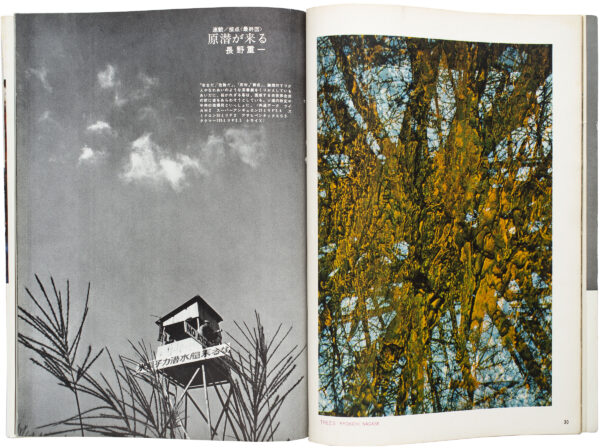

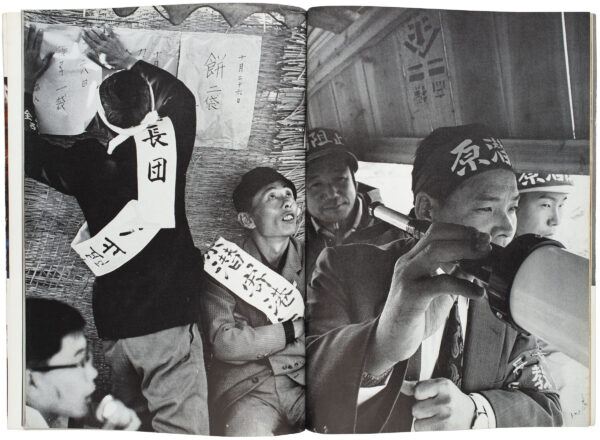

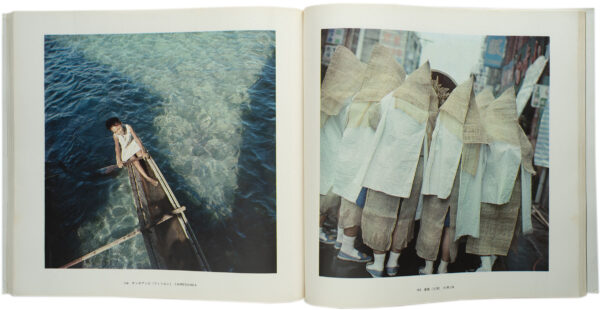

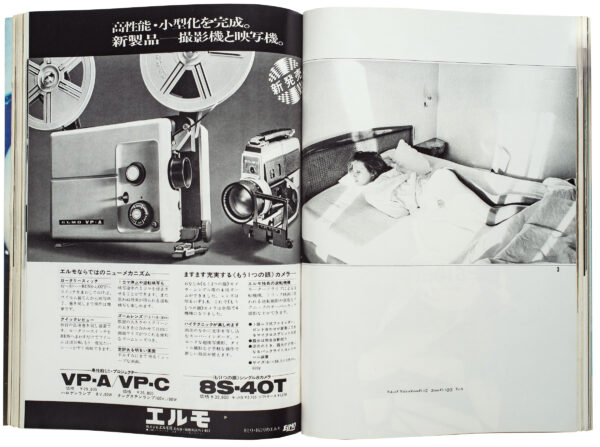

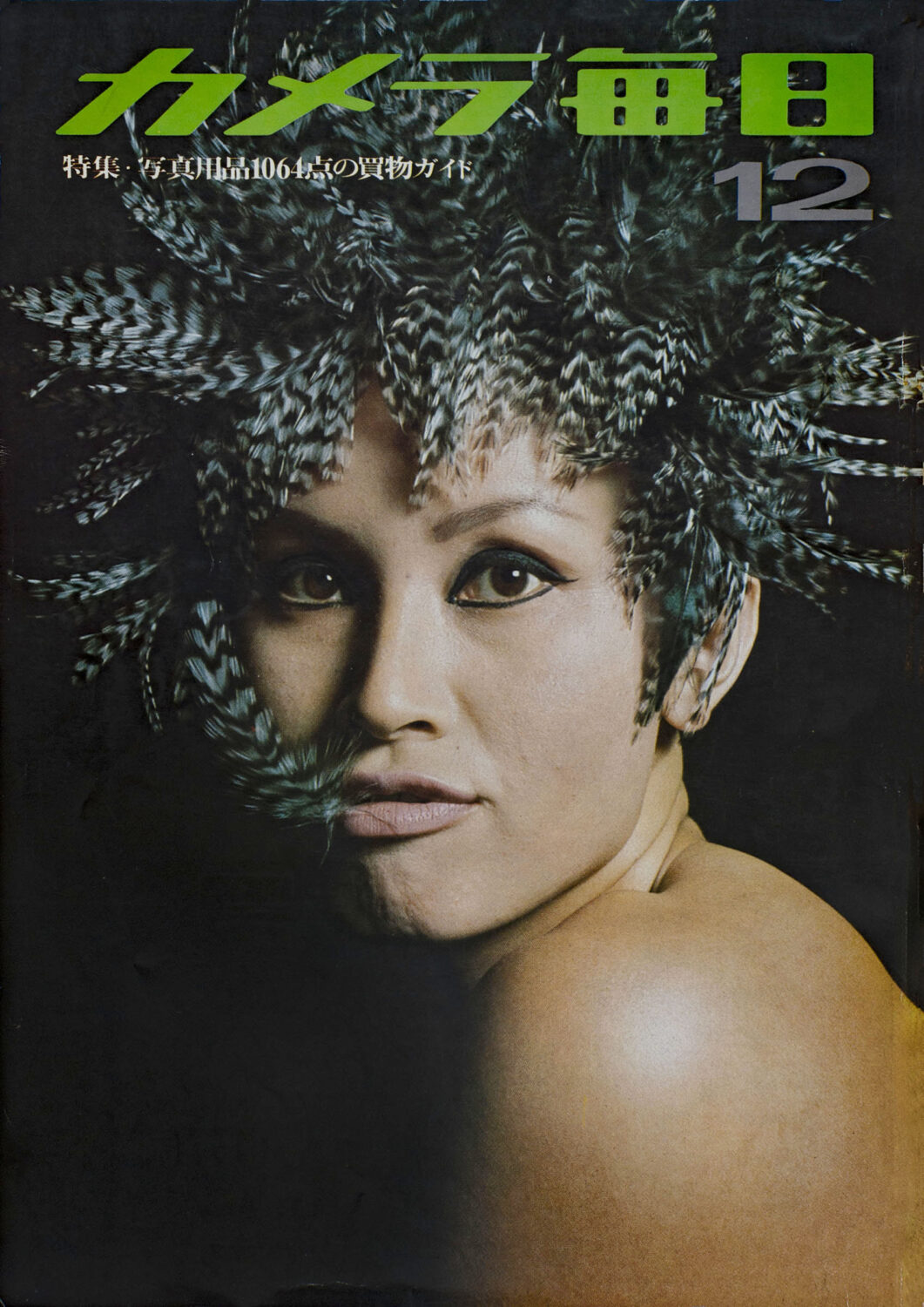

Camera Mainichi 12 - 1964

Editor: Yamagishi Shōji

Cover: Tatsuki, Yoshihiro

254 pages, gravure printing

.

Selection of content: Miss M, Tatsuki Yoshihiro 4 pages color / Speed Limit, Takanashi Yukata 5 pages color / Tree, Nagase Ryokichi 5 pages color / Atomic submarine, Nagano Shigeichi 6 pages b&w / Appearance, Fuji Hideki 2 pages b&w / Mr Hasegawa Kazuo, Takanashi Yukata b&w spread / Nat. Gymnasium at Yoyogi, Ishimoto Yashuhiro 5 pages b&w / Deserted Park, Tomatsu Shōmei 5 pages color / How one Town Greeted the Olympics , Fukase Masahisa 9 pages b&w / Dreamland, Ogawa Takayuki 7 pages b&w / Contest; winning works / experiment (4); expanding latitude through development / essay Endo Shusako / Photography supplies shopping guide / new product news / test report; 8 mm Elmo 8 /

Camera Mainichi 12 - 1964

Editor: Yamagishi Shōji

Cover: Tatsuki, Yoshihiro

254 pages, gravure printing

.

Selection of content: Miss M, Tatsuki Yoshihiro 4 pages color / Speed Limit, Takanashi Yukata 5 pages color / Tree, Nagase Ryokichi 5 pages color / Atomic submarine, Nagano Shigeichi 6 pages b&w / Appearance, Fuji Hideki 2 pages b&w / Mr Hasegawa Kazuo, Takanashi Yukata b&w spread / Nat. Gymnasium at Yoyogi, Ishimoto Yashuhiro 5 pages b&w / Deserted Park, Tomatsu Shōmei 5 pages color / How one Town Greeted the Olympics , Fukase Masahisa 9 pages b&w / Dreamland, Ogawa Takayuki 7 pages b&w / Contest; winning works / experiment (4); expanding latitude through development / essay Endo Shusako / Photography supplies shopping guide / new product news / test report; 8 mm Elmo 8 /

.

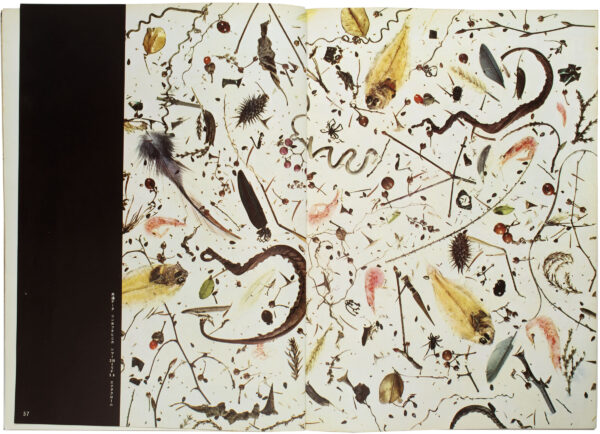

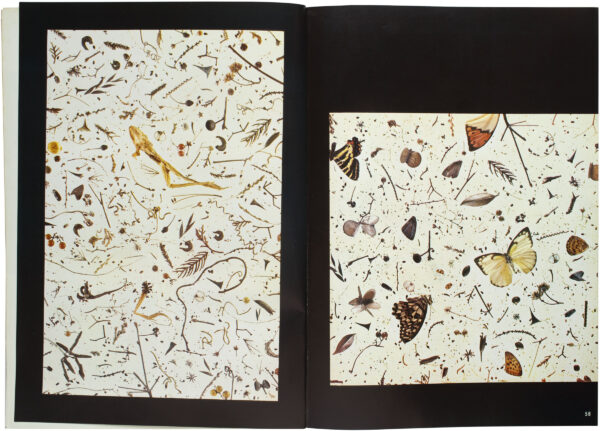

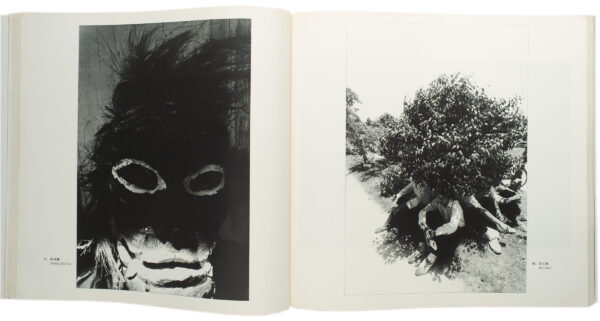

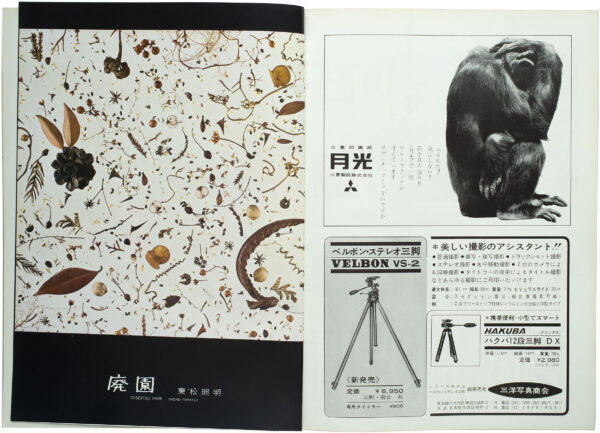

Tomatsu Shōmei, Deserted park. Also translated as abandoned garden or ruinous garden.

5 pages.

To my knowledge this is the first publication in color by Tomatsu.

He used to work in black and white, but during a long stay in Okinawa, around 1970, he switched to color photography, and after that never returned to monochrome.

Also uncommon for Tomatsu here is the use of a large format camera.

.

Tomatsu, walking in Musashino, Tokyo, collected materials, insects, picked nuts, scraps etc and carefully composed and photographing them.

Tomatsu, walking in Musashino, Tokyo, collected materials, insects, picked nuts, scraps etc and carefully composed and photographing them.

“It wasn’t something that was created from calculations, such as visualizing an image, but something that was created while I was doing it, and the moment when I was shocked and moved by the finished product, I clicked the shutter. It’s almost a spell, turning everything inside out “

.

Nagano Shigeichi, A nuclear submarine is coming, 6 pages b&w (final episode of the serial)

Protest against the visit of a nuclear submarine to the U.S. Navy base in Sasebo.

.

.

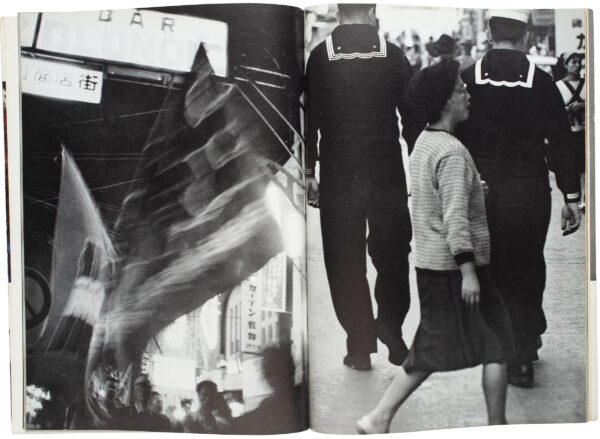

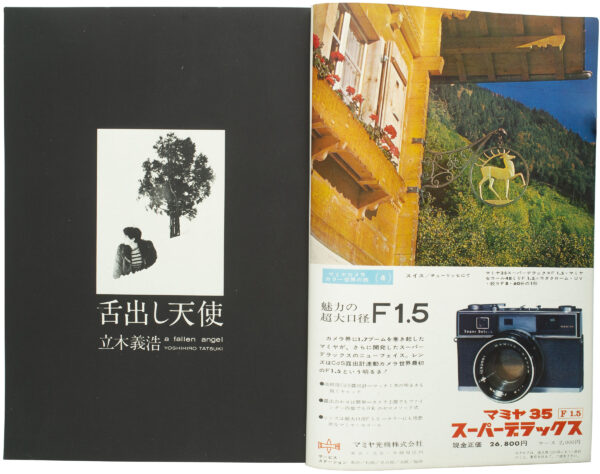

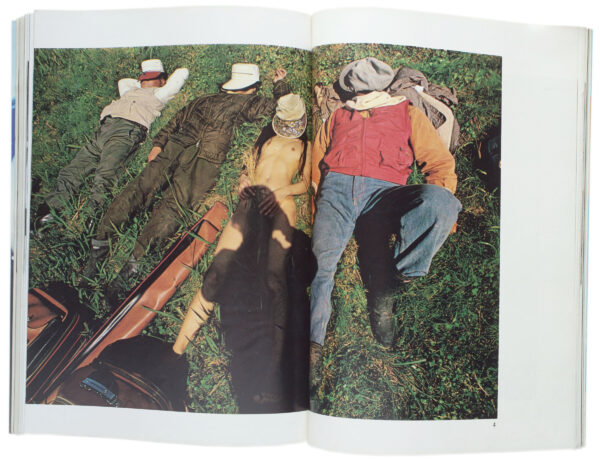

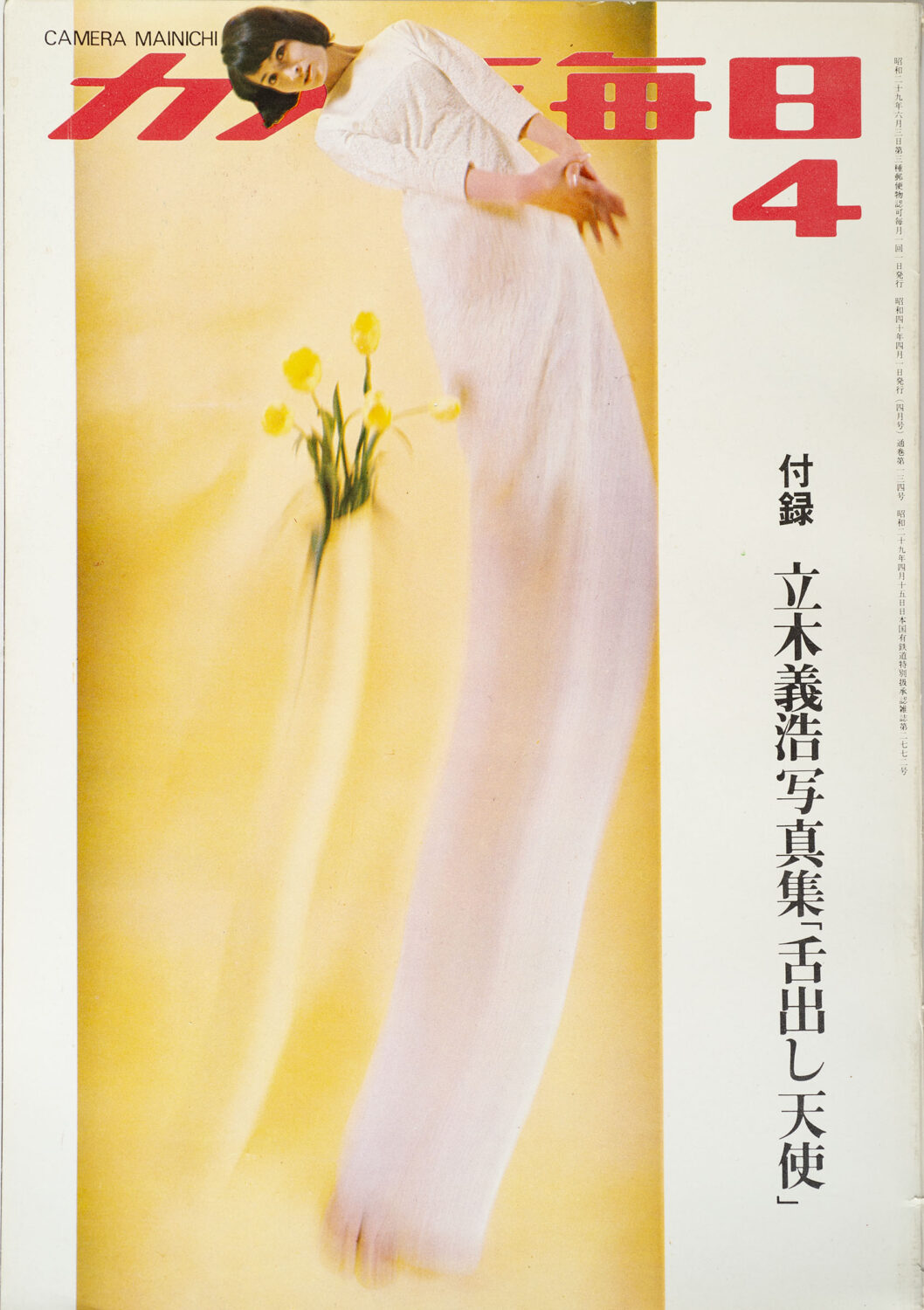

Camera Mainichi 4 - 1965

Chief editor: Kanazawa Hidenori. Editor: Yamagishi Shōji

Cover: Ishimoto Yasuhiro

254 pages, gravure printing

.

Selection of content:

Appendix: Tatsuki Yoshihiro “ Angel with tongue out” / Haneda Airport, Island of Two Dreams. (part 2 of the joint production series ; Ishimoto Yashuhito, Tomatsu Shōmei, Nagano Shigeichi 20 pages b&w / Akiyama Tadasuke - Sato Haruo ; Afternoon 5 pages color / Tatsuki Yoshihiro; Just Friends no.4 color spread / Ueda Shōji; Cow festival 4 pages color / Drift Ice Oze; Miki Keisuke 2 pages color / Higashi Yasuo; Relay series 4 “Young people in Ginza 5 pages b&w / Robert E. Wilson; New York street corner 2 pages b&w / Komori Yasuyuki; Spring comes again to the mountain 2 pages b&w / Toyama Takayuki; Illusion 4 pages b&w / This is how the documentary film “Tokyo Olympics” was filmed / Monthly photo contest winners / My experiment ‘reviewing 6x6 camera’s by Shinkawa Yukinobu / Birth of a nation; Keio University camera club 5 pages b&w / Using a new camera (87) Fujita 66 SQ / New product news ( Tokyo Camera Show.

Camera Mainichi 4 - 1965

Chief editor: Kanazawa Hidenori. Editor: Yamagishi Shōji

Cover: Ishimoto Yasuhiro

254 pages, gravure printing

.

Selection of content:

Appendix: Tatsuki Yoshihiro “ Angel with tongue out” / Haneda Airport, Island of Two Dreams. (part 2 of the joint production series ; Ishimoto Yashuhito, Tomatsu Shōmei, Nagano Shigeichi 20 pages b&w / Akiyama Tadasuke - Sato Haruo ; Afternoon 5 pages color / Tatsuki Yoshihiro; Just Friends no.4 color spread / Ueda Shōji; Cow festival 4 pages color / Drift Ice Oze; Miki Keisuke 2 pages color / Higashi Yasuo; Relay series 4 “Young people in Ginza 5 pages b&w / Robert E. Wilson; New York street corner 2 pages b&w / Komori Yasuyuki; Spring comes again to the mountain 2 pages b&w / Toyama Takayuki; Illusion 4 pages b&w / This is how the documentary film “Tokyo Olympics” was filmed / Monthly photo contest winners / My experiment ‘reviewing 6x6 camera’s by Shinkawa Yukinobu / Birth of a nation; Keio University camera club 5 pages b&w / Using a new camera (87) Fujita 66 SQ / New product news ( Tokyo Camera Show.

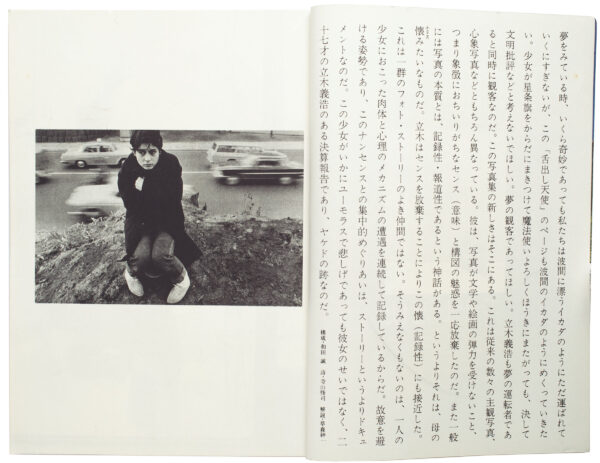

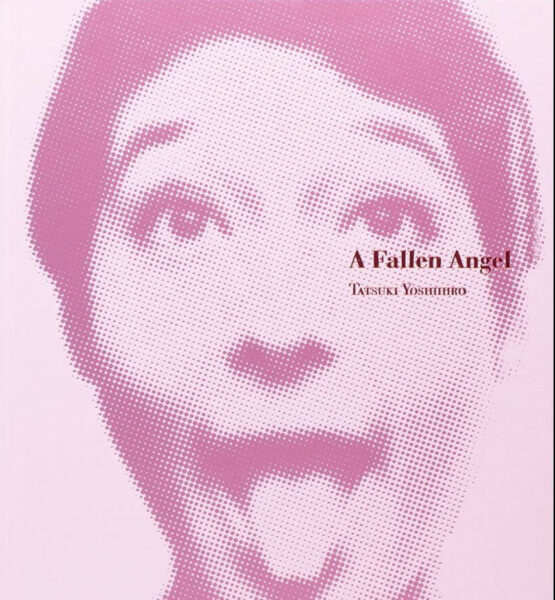

Fallen Angel (Shita Dashi Tenshi - 舌出し天使 )* appeared in the April 1965 issue of Camera Mainichi. A collaboration between Tatsuki Yoshihiro, a budding advertising photographer, and the poet Terayama Shūji, Fallen Angel marked an important turning point in both the history of Japan’s editorial design and photography.

(….)

Camera Mainichi, which had been a news-orientated publication, started to regularly feature the work of young advertisement photographers,

Editor Yamagishi Shōji was responsible for this shift, and with Fallen Angel he set a new standard for what was possible in a camera magazine.

This issue’s cover reads, “Appendix: Tatsuki Yoshihiro’s photobook Fallen Angel”. This special feature was tantamount to an entire photobook. Its scale in the magazine was unprecedented, encompassing fifty-six pages , with lay-out by Wada Makoto and commentary by Kusamori Shin’ichi.

(……)

This is just a small selection of the excellent essay about this issue by Toda Masako in Japanese Photography Magazines 1880s-1980s, Goliga Books 2022

* Note by Ivan Vartanian in his newsletter October 2020 about Tatsuki Yoshihiro:

舌出し天使 (translated to Fallen Angel) focused on a young woman being emotive and playful for the camera. In many instances, she short crop and somewhat androdyous build make her seem that much younger. The original Japanese title shita dashi tenshi translates literally to an ‘angel sticking out its tongue’ , which underscores better the youthful charge of the photography (as opposed to the more lyrical translation that was made at the time).

https://goliga.com/newsletter/tatsuki-selfie

.

It is important to note that this work was not an excerpt from an exhibition or the digest of an extant photobook; rather, it was shot specifically for these spreads. ( Toda Masako in Japanese Photography Magazines 1880s-1980s )

.

Eventually, in 1971, a selection of Fallen Angel, along with 2 other series, was published by Chuo Koronsha in ‘The Image Today Series’.

.

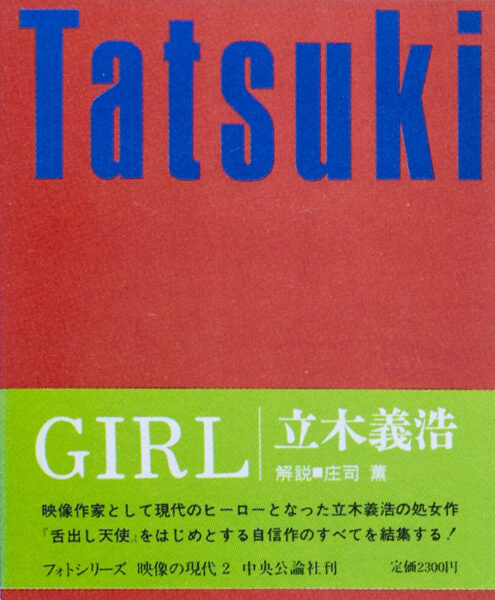

Tatsuki Yoshihiro: Girl

The Image Today Series, no. 2

Publisher: Chuo Koronsha, Tokyo. 1971

26,6 x 22,1 cm. Hardcover, dust jacket with obi, acetate sleeve

120 pages, photographes in offset

A Fallen Angel (models: Yamazoe Noriko, etc.),

GIRL (model: Koizumi Hitomi),

Kikai-jima (model: Kageyama Misuzu)

Tatsuki Yoshihiro: Girl

The Image Today Series, no. 2

Publisher: Chuo Koronsha, Tokyo. 1971

26,6 x 22,1 cm. Hardcover, dust jacket with obi, acetate sleeve

120 pages, photographes in offset

A Fallen Angel (models: Yamazoe Noriko, etc.),

GIRL (model: Koizumi Hitomi),

Kikai-jima (model: Kageyama Misuzu)

A Fallen Angel, 2018 edition by LibroArte, with 62 photos published at that time, plus 24 unrecorded photos.

.

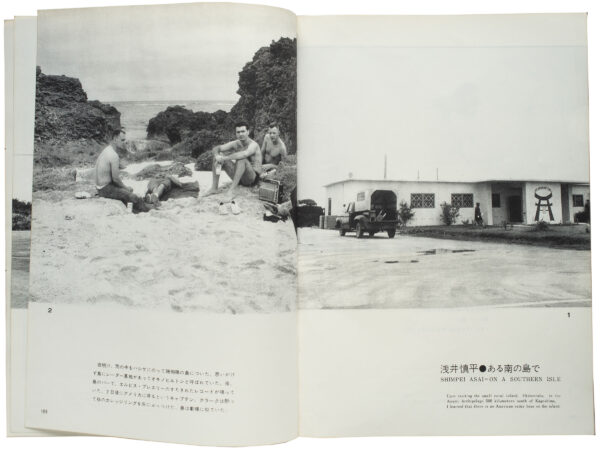

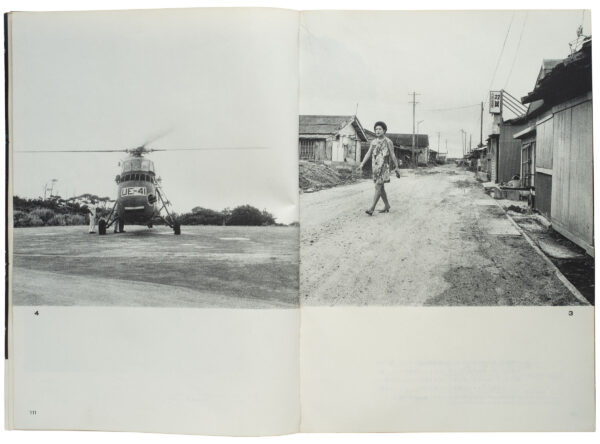

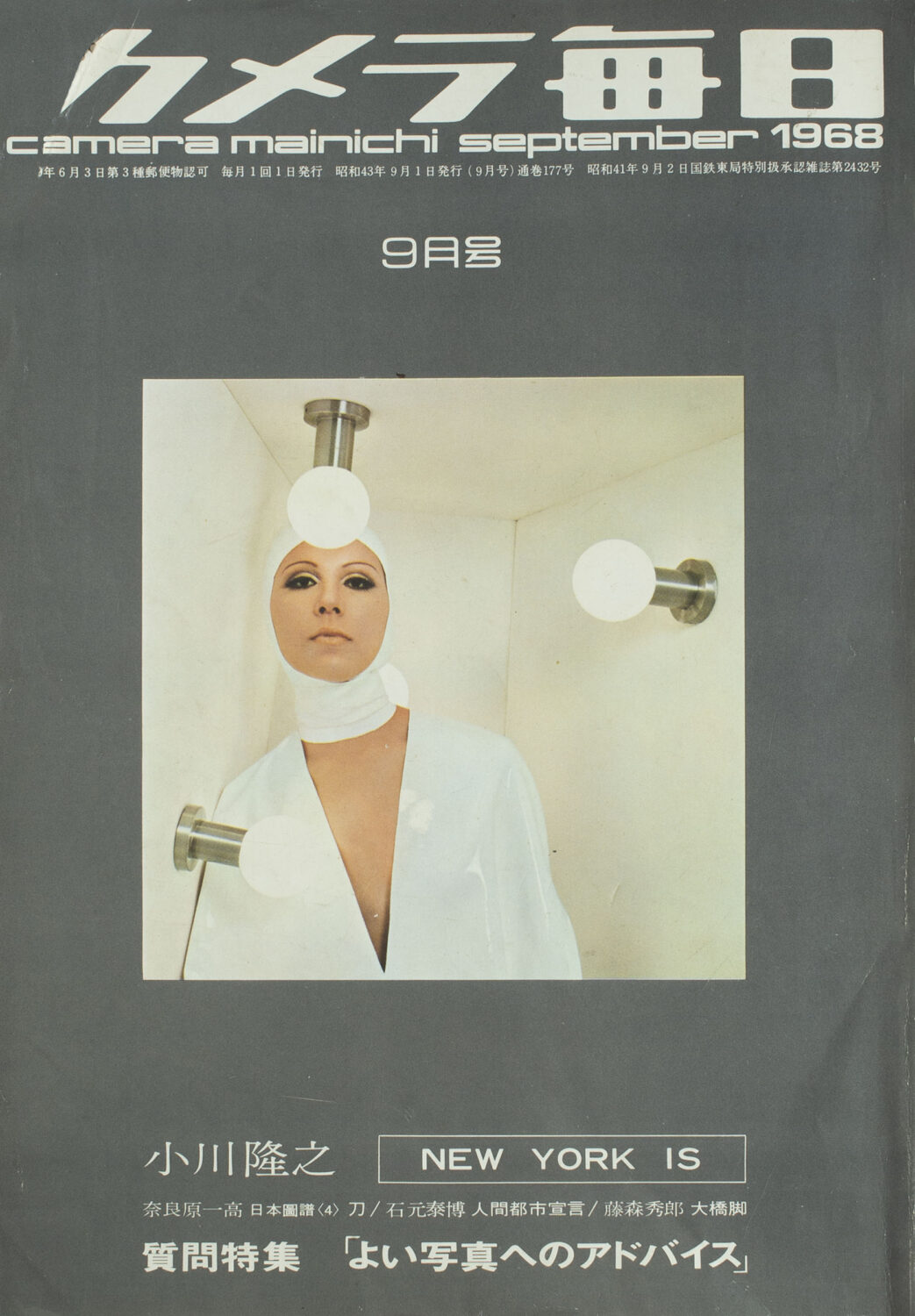

Camera Mainichi 9-1968

Chief editor: Kanazawa Hidenori.

Editor: Yamagishi Shōji

Cover: Sato Akira

240 pages, gravure printing

Selection of content:

New York Is, Ogawa Takayuki, 32 pages b&w / Person without Person, Ishimoto Yashuhiro, 8 pages color /Building a highway, Fujimori Hidero, 7 pages color / Japanesque (4) Katana swords, Narahara Ikko, 13 pages b&w / Island of lava - Miyakejima, Shimotsu Takayuki 5 pages b&w / Cicus performers, Konishi Umihiko, 4 pages b&w / Wind ( Fujin) Nagahama Osamu, 2 pages b&w / On a certain Southern Isle, Asai Shimpei, 5 pages b&w / Monthly Photo Contest winners / Commentary; I want a evocative photo- is contemporary photography a personal novel?, Kaji Yusuke / Using a new camera, Petricolor 35 / New product introduction / Photography and electricity (9), the selenium exposure meter /

Camera Mainichi 9-1968

Chief editor: Kanazawa Hidenori.

Editor: Yamagishi Shōji

Cover: Sato Akira

240 pages, gravure printing

Selection of content:

New York Is, Ogawa Takayuki, 32 pages b&w / Person without Person, Ishimoto Yashuhiro, 8 pages color /Building a highway, Fujimori Hidero, 7 pages color / Japanesque (4) Katana swords, Narahara Ikko, 13 pages b&w / Island of lava - Miyakejima, Shimotsu Takayuki 5 pages b&w / Cicus performers, Konishi Umihiko, 4 pages b&w / Wind ( Fujin) Nagahama Osamu, 2 pages b&w / On a certain Southern Isle, Asai Shimpei, 5 pages b&w / Monthly Photo Contest winners / Commentary; I want a evocative photo- is contemporary photography a personal novel?, Kaji Yusuke / Using a new camera, Petricolor 35 / New product introduction / Photography and electricity (9), the selenium exposure meter /

.

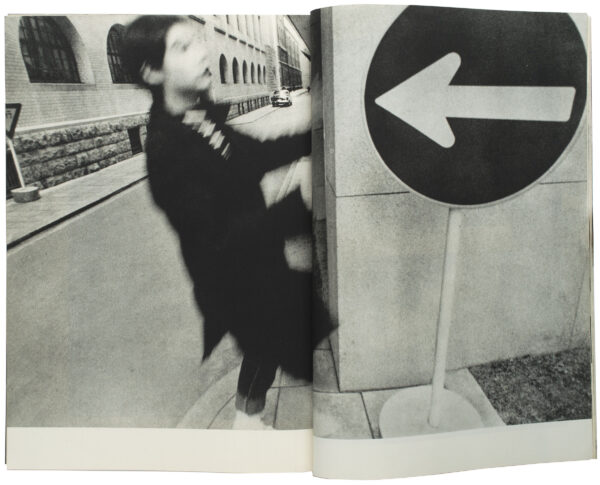

In this issue again ( see Camera Mainichi April 1965, above ) the equivalent of a photobook published in a magazine; 32 pages in gravure print of Ogawa Takayuki’s story ’ New York Is ’

But from this months edition I choose the work of Asai Shimpei, who visited a small coral island, Okinourabujima, 50 kilometers north of Okinawa, which housed an American radar base.

Asai Shimpei, On a southern island, 5 pages b&w

.

.

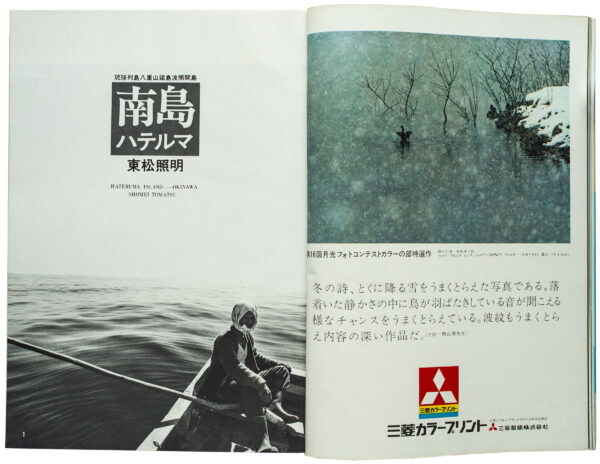

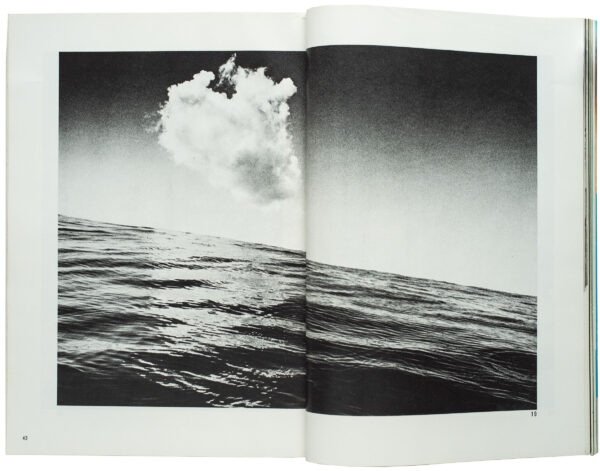

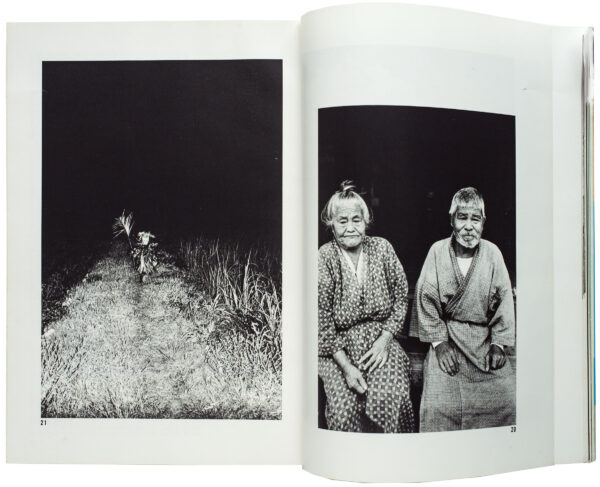

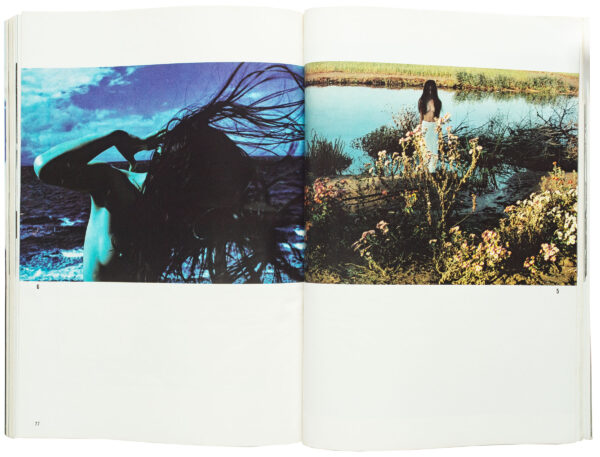

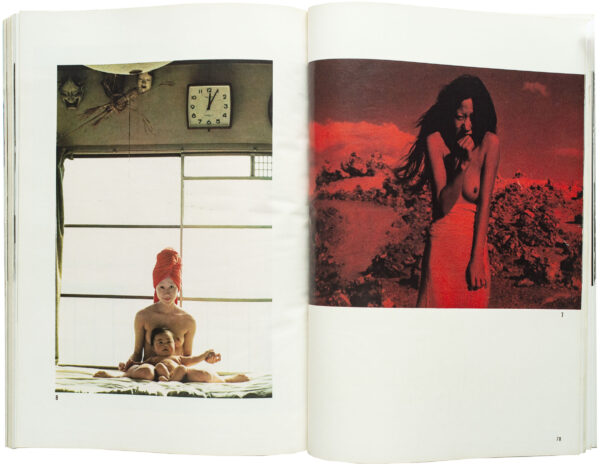

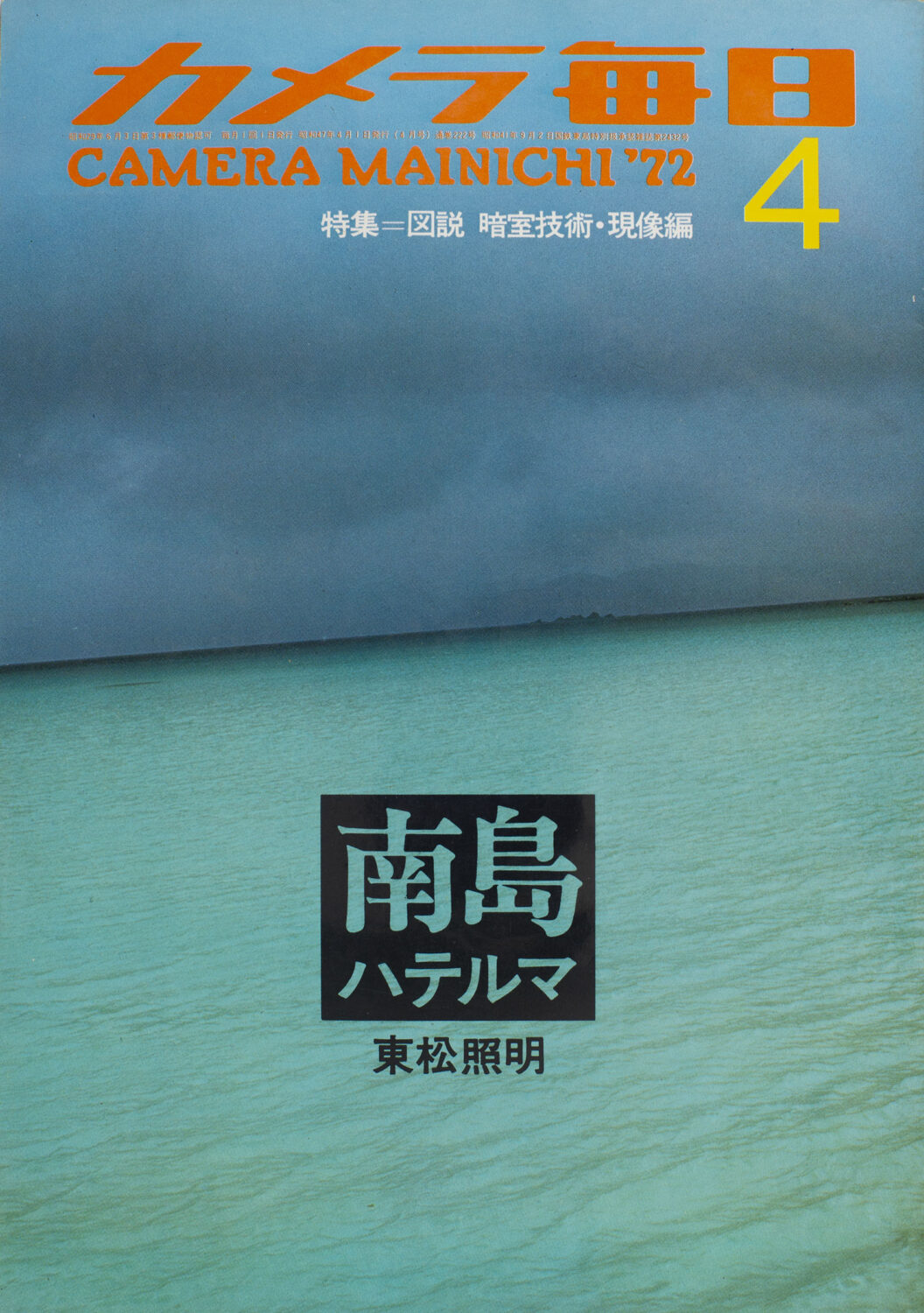

Camera Mainichi 1972 - 4

Chief editor: Yoda Takayoshi

Editor: Yamagishi Shōji

Cover: Tomatsu Shōmei

267 pages, gravure printing

Selection of content:

Hateruma Island. Okinawa, Tomatsu, Shōmei, 24 pages b&w / Ireland, Hagiwara Hideoki, 8 pages b&w / A Play 6, Fukase Masahisa, 11 pages color / From noon to night, Tanaka Chotoku, 5 pages color / A port town 2, Akiyama Ryoji, 7 pages b&w / Nadia 6, Sawatari Hajime, 3 pages b&w / North Japan, Nishimura Tamiko, 7 pages b&w / Country life, Seko Masaji, 5 pages b&w / Darkroom special / Tokyo camera show / New product news /Camera Mainichi Monthly Photo Contest /

Camera Mainichi 1972 - 4

Chief editor: Yoda Takayoshi

Editor: Yamagishi Shōji

Cover: Tomatsu Shōmei

267 pages, gravure printing

Selection of content:

Hateruma Island. Okinawa, Tomatsu, Shōmei, 24 pages b&w / Ireland, Hagiwara Hideoki, 8 pages b&w / A Play 6, Fukase Masahisa, 11 pages color / From noon to night, Tanaka Chotoku, 5 pages color / A port town 2, Akiyama Ryoji, 7 pages b&w / Nadia 6, Sawatari Hajime, 3 pages b&w / North Japan, Nishimura Tamiko, 7 pages b&w / Country life, Seko Masaji, 5 pages b&w / Darkroom special / Tokyo camera show / New product news /Camera Mainichi Monthly Photo Contest /

.

Tomatsu Shōmei; Hateruma Island, Okinawa. 24 pages b&w

Tomatsu’s first encounter with Okinawa was in 1969. This photo reportage appeared in the June and July 1969 issues of Asahi Camera, and was then published as a separate - and definitely his most political - book: ‘Okinawa, Okinawa, Okinawa.’

( see: Asahi Camera July 1969 )

Tomatsu: I first went to Okinawa in 1969. Like a pilgrim I had visited all the American bases from Hokkaido to Kyushu, and Okinawa represented the one remaining holy place.

There are so many bases concentrated in Okinawa that it was often said; “There aren’t bases in Okinawa, Okinawa is inside a bases.”

According to Tomatsu the character of postwar Japan could be summed up with the word ‘Americanization’.

He expected Okinawa, ( it had been under a U.S. military government since 1945, so more then a quarter of a century) to be even more ‘Americanized’ then Japan itself.

But he found a culture and a beauty which astonished him.

I wrote at the time that “I did not come to Okinawa but returned to Japan, and I will not be returning to Tokyo but going to America”.

The natural features of Okinawa are beautiful - the transparant blue sky, the sea so blue it looks as if it could dye your skin. The reflection of the sun pouring onto the coral reefs turns the sea a spectrum of colors: horizon blue, emerald, peacock green, cobalt. The sun burns, the wind shines…. In Okinawa, it seemed a natural step to switch to color photography….but even after returning to Tokyo, I did not go back to monochrome….I realized later that this was because of my fixation on America had weakened. America flashes into and out of view in black and white. In color, America’s presence is diminished.

His long stay in Okinawa permanently changed Tomatsu's photography. Not only did he switch from monochrome to color, but social or political issues no longer played a significant role in his work.

About the transformation in Tomatsu's work, John W Dower writes ;

(….)

Tomatsu quite literally discovered color, thereafter he shot less and less in black and white. He had found people, places, and subjects to treasure and celebrate.

To a certain degree, these intensely personal developments held a mirror to the times. Even before the ‘reversion’ of Okinawa could be assessed, before the fighting in Indochine actually ended, before the student demonstrators put away their banners, the counterculture had begun to melt away. The early 1970s were a watershed, not merely in Japan, but throughout the developed world. The sort of restless, unsettling vision Tomatsu exemplified throughout the 1950s and 1960s would become much rarer - everywhere - thereafter.

In Japan itself, iconoclasm did not disappear entirely, of course, and the debate about ‘being Japanese’ never ceased to be fiercely contested ground.

John W Dower, ‘Contested ground: Shōmei Tōmatsu and the search for identity in postwar Japan’. ( Shōmei Tōmatsu, Skin of the Nation, 2004 San Francisco Museum of Modern Art )

.

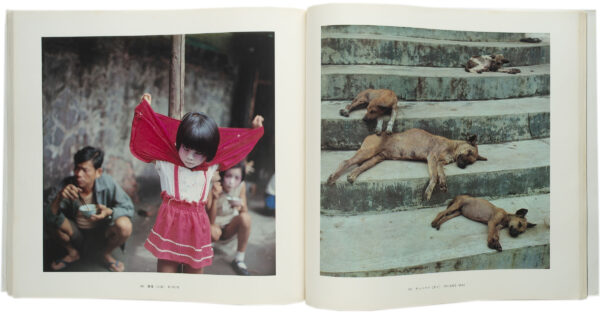

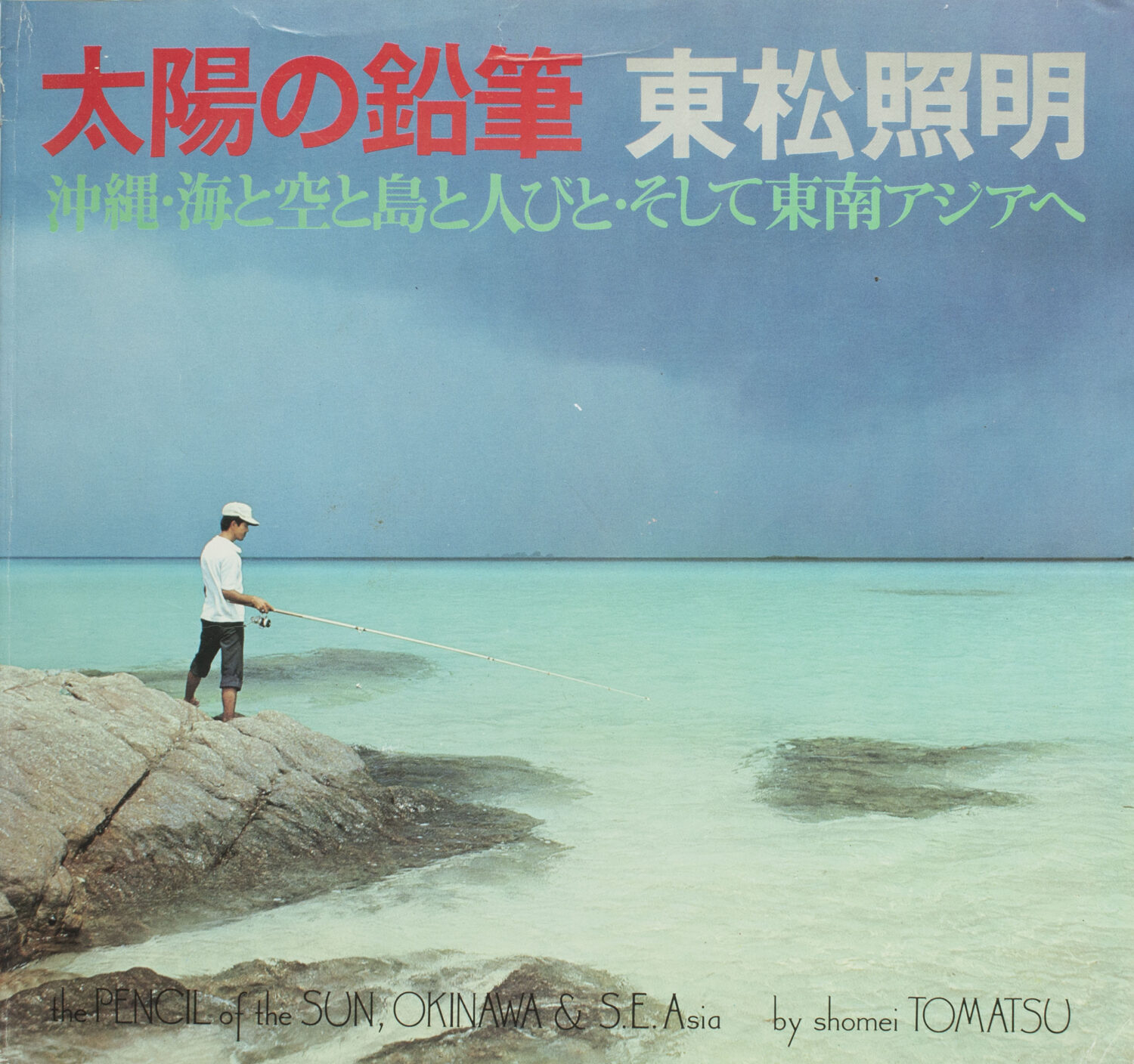

東松 照明 / Tomatsu Shōmei

太陽の鉛筆 / The Pencil of the Sun,Okinawa & S.E.Asia

Mainichi Shimbunsha, Tokyo, 1975

24,5 x 26 cm, softcover

238 pages, photographes in offset.

Editor: Kitajima Noboro

The first half consists of black-and-white photographs of the islands of Okinawa, and the second half consists of color photographs of Southeast Asian countries.

東松 照明 / Tomatsu Shōmei

太陽の鉛筆 / The Pencil of the Sun,Okinawa & S.E.Asia

Mainichi Shimbunsha, Tokyo, 1975

24,5 x 26 cm, softcover

238 pages, photographes in offset.

Editor: Kitajima Noboro

The first half consists of black-and-white photographs of the islands of Okinawa, and the second half consists of color photographs of Southeast Asian countries.

.

Much more to enjoy in this months edition;

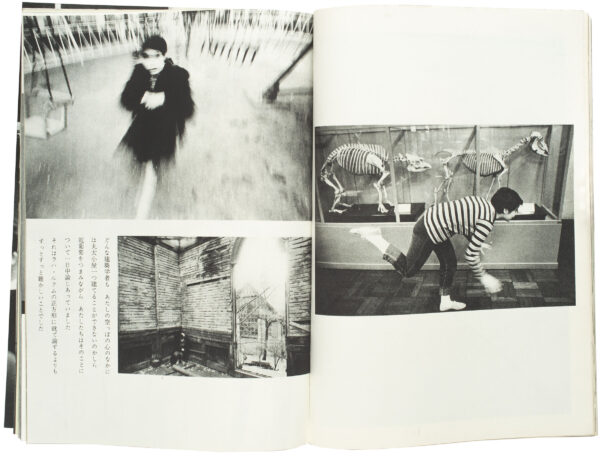

11 pages Fukase Masahisa, A Play 6

(….)

These works were published in eight successive parts over a period of three years in Camera Mainichi, under the title ‘A Play’.

In the first three parts, Fukase overlays multi-exposure images of the countryside and of the city with stage photographs taken during performances of Jōkyō Gekijo, an underground ‘situationist theater’ company run by Jurō Kara, and of Ankoku-butoh shadow dancing, a new form of expression set up by Hijikata Tatsumi. Fukase’s layering technique consisted of rewinding an already exposed film in order to take new photographs on top; this meant that; “I had no idea what I had photographed nor where until I developed them”.

By the fourth part of ‘A Play’, there was a radical shift in style.

Fukase abondoned photomontage in favor of shots taken directly within his surroundings, the Matsubara residential complex. The people featured in this series are his carp-fishing friends, as well as Ashikawa Yoko and Kobayashi Saga, dancers who worked under the supervision of Hijikata Tatsumi.

Fukase describes their presence within the banal suburban landscape as follows: “You end up no longer seeing a landscape as a result of having it in front of your eyes every day, so nudity becomes a necessary stimulant . This, therefor, is fictitious.”

(….)

Kosuga Tomo in ‘Masahisa Fukase’, Edition Xavier Barral 2018

Kosuga Tomo is director Masahisa Fukase Archives, Tokyo.

.

.

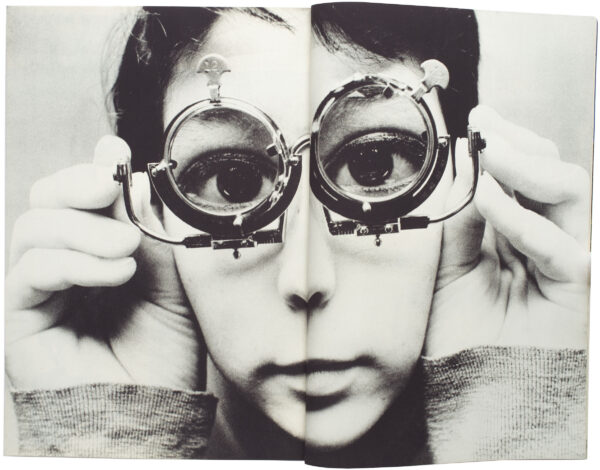

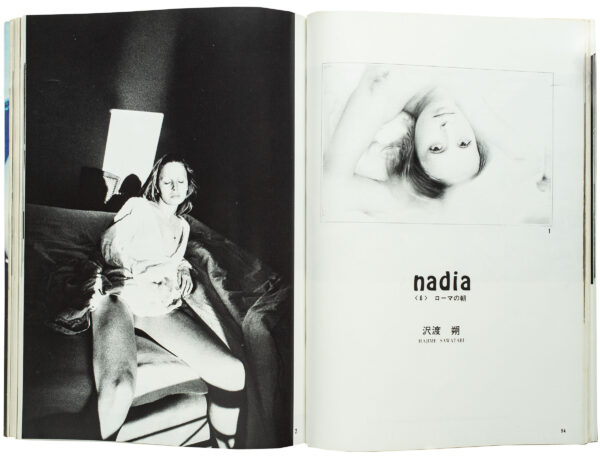

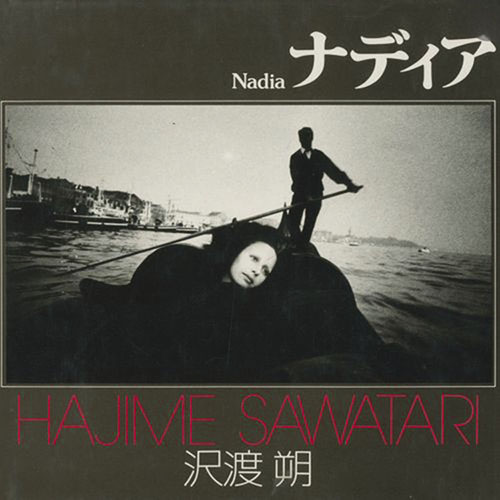

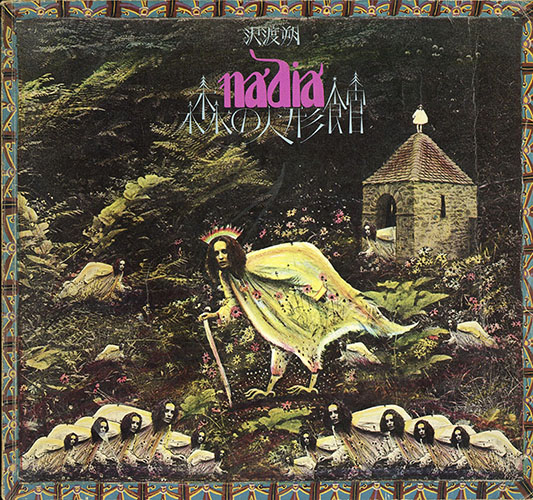

3 pages Sawatari Hajime, Nadia 6

.

Sawatari Hajime's first photo book was a special edition of Camera Mainichi, as a part of the Private series of ‘talent” books, published by Mainichi Shimbunsha.

Nadia was the third and final volume of the series.

It is a compilation of the "NADIA" series, which ran in Camera Mainichi from the November 1971 to November 1972 issues, and is made up of five parts: Forest Doll Museum, Wings of the Night, Travel in Italy, Inside the Mirror, and Winter. This is a place where fiction and reality intersect, made possible by his encounter with Nadia Galli, a model from northern Italy.

As the editor Shoji Yamagishi wrote at the end of this book, which was created using fashion photographic techniques, Nadia's various facial expressions and appearances, while the truth and the illusion are intermingled between the fiction and documentary gorges, are projected in various scenes.

.

Sawatari Hajime : Nadia

沢渡朔 : ナディア 森の人形館 (Japanese title: NADIA Forest Doll Museum)

1973, Mainichi Shimbunsha

108 pages - 27,8 x 30 cm, 90 black and white photographs, printed in gravure

softcover

Editor: Yamagishi Shōji

Cover Design: Horiuchi Sei’ichi

Cover illustration: Suzuki Kōji

Layout: Honda Shinji

Text: Mutsuo Takahashi , Nadia Galli

Sawatari Hajime : Nadia

沢渡朔 : ナディア 森の人形館 (Japanese title: NADIA Forest Doll Museum)

1973, Mainichi Shimbunsha

108 pages - 27,8 x 30 cm, 90 black and white photographs, printed in gravure

softcover

Editor: Yamagishi Shōji

Cover Design: Horiuchi Sei’ichi

Cover illustration: Suzuki Kōji

Layout: Honda Shinji

Text: Mutsuo Takahashi , Nadia Galli

Sawatari Hajime: Nadia

1977, Asahi Sonorama

20,8 x 22 cm, 120 pages, photographs printed in gravure

Hardcover, dustjacket

Volume 5 in the Sonorama Photography Anthology serie